The sitting President has unusually broad authority to direct declassification and public release of federal information through an executive order. That authority is at its most expansive for material controlled under the general classification system that exists by executive order.

It is limited where Congress has spoken by statute. For Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena, that means a President can order government wide searches, set deadlines, reduce redactions, and compel routine disclosure of many UAP related records.

The President cannot use an executive order to sweep aside statutory secrecy regimes such as the Atomic Energy Act’s “Restricted Data,” or the Intelligence Identities Protection Act’s bars on outing covert officers.

The separation of powers story is the real map. This explainer lays out, with citations, what a President can do now, what would require legislation, what could be released quickly, and why a White House might or might not pull this lever.

Who holds the declassification keys today

The United States classification system is created by executive order. The governing order is Executive Order 13526, which “prescribes a uniform system for classifying, safeguarding, and declassifying national security information,” and is implemented across agencies by 32 C.F.R. part 2001.

In plain terms, the President sets the rules for most classified information and can change those rules. (National Archives)

Courts have recognized that the President’s power to classify and control access to national security information stems from Article II unless Congress has specifically provided otherwise.

The Supreme Court summarized this frame in Department of the Navy v. Egan when it noted that the President’s authority to classify and control access “flows primarily from this constitutional investment of power in the President” and that courts will not intrude “unless Congress has specifically provided otherwise.”

That sentence is the backbone for how declassification works inside the executive branch. (Legal Information Institute)

Two Additional Pieces Complete the Legal Picture.

- Executive Order 13526 does not trump statutes. It says so on its face.

Section 6.2 states that nothing in the order supersedes requirements made by or under the Atomic Energy Act or the National Security Act. That clause codifies the obvious constitutional rule that a President cannot use an order to repeal or ignore an Act of Congress. (National Archives) - When courts face litigation over the government’s refusal to disclose sensitive information, the state secrets privilege and related doctrines can bar disclosure even outside the classification system.

The modern framework begins with United States v. Reynolds and remains active in recent cases like United States v. Zubaydah. Presidents can choose not to assert this privilege in a given case, but where the government asserts it, courts apply specific tests and often defer. (Legal Information Institute)

The baseline therefore is simple. A President can direct release across the large universe of information governed by executive order. Congress can cabin that authority where it enacts clear rules. And the courts police edge cases through privileges and remedies that operate outside the order.

What an Executive Order Can Do on UAP Records this Year

Because UAP touches many agencies and sensor systems, the practical power of an executive order is the ability to coordinate, calendar, and standardize. Here are the main tools a President can deploy under current law, with the relevant authorities.

- Direct an immediate inventory of UAP holdings and set deadlines

Executive Order 13526 and its implementing directive already require agencies to mark, manage, and review classified information, and they create a process called mandatory declassification review. A new UAP specific order can require agency heads to produce a catalog of UAP records, set ninety or one hundred eighty day deadlines for declassification decisions, and elevate any disputes to the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel for fast track review. The Panel exists by order and already adjudicates classification challenges and appeals. (National Archives) - Create a centralized UAP Records Collection at the National Archives

Congress considered a UAP records collection model in 2023. Even without new law, the President can direct agencies to transmit releasable UAP records to the Archivist under the existing executive order framework, publish indexing standards, and require rolling public releases on a set calendar. That is exactly how earlier subject driven disclosure efforts achieved momentum. (Congress.gov) - Rewrite classification guidance and reduce rote redactions

Under 32 C.F.R. part 2001 and E.O. 13526, agencies operate with classification guides that often lag reality. An order can compel immediate revision of guides so that UAP related materials which do not reveal current sources and methods are presumptively unclassified. The President can set a presumption of disclosure for UAP records, subject to specific, narrow exceptions already recognized by law. (National Archives) - Prioritize UAP MDR and FOIA queues

Mandatory declassification review is part of the order driven system, and Freedom of Information Act processing is statutory. A President cannot rewrite FOIA by order, but can direct agencies to prioritize UAP MDRs and FOIA searches, and to favor discretionary releases where doing so will not foreseeably harm protected interests. Agencies already publish FOIA rules that recognize this discretion. (National Archives) - Compel uniform handling of imagery and sensor videos

An order can require that legacy UAP videos and imagery be reviewed under a uniform harm test with consistent marking and redaction practices. The ISOO marking guidance and the order’s chapter on handling of classified information give the White House a ready playbook to do this. (National Archives) - Decontrol or downgrade information that was only classified under the order

If UAP related information was classified solely under executive order authority, a President can direct that it be declassified or downgraded, immediately or on a schedule. That is routine practice in other topical releases. (National Archives) - Task the Department of War and the DNI

A President can instruct the Department of War and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to coordinate interagency release plans, identify UAP content that can be separated from sensitive collection details, and publish regular transparency reports. The ODNI’s role in intelligence community policy and the AARO portfolio make this a straightforward directive. (Director of National Intelligence)

What an Executive Order Cannot Do

Even the most aggressive transparency order cannot cross certain lines without Congress.

- Atomic Energy Act material

Information that meets the statutory definition of “Restricted Data” or “Formerly Restricted Data” is classified by law. Declassification follows processes in 10 C.F.R. part 1045 and requires Department of Energy and Department of Defense action under the Atomic Energy Act. Executive Order 13526 is explicit that nothing in the order supersedes these requirements. If a UAP record commingles nuclear weapon design or production information, an executive order alone cannot declassify it. (eCFR) - Statutes that protect identities and sources

The Intelligence Identities Protection Act criminalizes disclosures that identify certain covert officers and sources. That regime exists by statute separate from the order. A President can direct redaction strategies that protect identities while releasing the rest, but cannot use an order to make prohibited disclosures legal. (Legal Information Institute) - Special Access Programs have notification rules

Declassifying or altering access to Department of Defense special access programs has congressional notice requirements. An order can initiate changes, but the process must respect these statutory hooks. (Legal Information Institute) - State secrets litigation cannot be mooted by order alone

When the government invokes the state secrets privilege in court, judges apply standards independent of the order. A President can choose a disclosure posture, but once litigation is live the privilege operates under case law. (Legal Information Institute)

A Data Oriented Map of What Could be Released Under a UAP Transparency Order

Records likely releasable with tailored redactions

- Historical incident reports, logs, and narrative summaries that do not reveal live sources and methods. These are often subject to routine declassification at the twenty five year mark anyway under E.O. 13526. (National Archives)

- Legacy cockpit videos and tracking displays where sensor metadata can be sanitized. The order and implementing directive allow for declassification by removing details that would harm collection. (National Archives)

- Budgets and contracts that show the fact of UAP related research without sensitive performance details. FOIA and MDR practice routinely release contract headers and line items while withholding proprietary details under different exemptions. (Legal Information Institute)

- AARO analytic products and case catalogs that aggregate in unclassified format what the government already knows, with classified annexes held back. The AARO mission already contemplates public reporting. (AARO)

Records that would require careful review or may remain withheld

- Modern sensor data whose time tags and waveform signatures reveal collection capabilities. Review is possible, but some data will stay classified. The order and ISOO directive give agencies clear grounds to protect this material. (National Archives)

- Anything mixing nuclear weapons design or production information and UAP topics, which would be governed by the Atomic Energy Act. Even if a UAP encounter occurred near a nuclear asset, details that fall within “Restricted Data” must pass through DOE and DOD processes. (eCFR)

- Identities of human sources and covert personnel, which are protected by statute independent of classification status. (Legal Information Institute)

- Details of active special access programs. Congress must be notified before public declassification of a SAP or a major change in its status. (Legal Information Institute)

Reasons a President Would use an Executive Order for UAP Transparency

To establish one set of rules across many agencies

UAP intersects defense, intelligence, aviation safety, and science. An order can impose a single playbook for classification guides, redaction standards, and release calendars. That reduces contradictory decisions across the government. (National Archives)

To get ahead of Congress and set the frame

In 2023 senators proposed a UAP records collection and presumption of disclosure at the National Archives. A White House that moves first with an order can shape the process and show it takes transparency seriously, while protecting equities through targeted exceptions already recognized by law. (Congress.gov)

To reduce FOIA friction using existing discretion

FOIA allows agencies to make discretionary releases where doing so does not harm protected interests. A President can direct agencies to exercise that discretion for UAP records and to prioritize these queues, which helps the public and relieves backlogs. (Legal Information Institute)

To demonstrate leadership on a subject of sustained public interest

A consistent release plan that publishes new tranches on a schedule builds credibility and lowers the temperature of speculation. The ISCAP and MDR processes already exist to handle disputes in a structured way. (National Archives)

Reasons a President Would Hesitate

Protection of sensitive collection

Modern military and intelligence sensors are expensive and fragile to compromise. Time tagged video or raw waveform data can reveal ranges and modes. Agencies will argue, often persuasively, that some UAP adjacent data should remain classified. The order permits that where harm can be articulated. (National Archives)

Foreign partner equities

Allied sharing agreements and foreign government information rules add constraints that the order recognizes. Release of data supplied by partners often requires their consent. (National Archives)

Statutory hard stops

Atomic Energy Act material, covert identities, and similar statutory lanes cannot be overridden by executive order. Pushing into these zones would trigger legal conflict and could fail in court. (eCFR)

Competing priorities and limited staff bandwidth

A government wide declassification push consumes time. Agencies must search archives, review equities, coordinate with the Archives, and prepare public releases. Even with a President’s directive, real capacity limits apply. The National Archives and ISOO publish the processes, but they cannot conjure reviewers that do not exist. (National Archives)

A Realistic Executive Order Blueprint for Disclosure

If the White House chose to act, a practical UAP transparency order would include seven core sections.

- Purpose and policy

Declare a presumption of disclosure for UAP records that do not identify protected sources, reveal modern collection techniques, or fall into statutory categories like Restricted Data or protected identities. Anchor this in E.O. 13526’s existing framework and 32 C.F.R. part 2001. (National Archives) - Definitions and scope

Adopt the government’s standard UAP definition and identify covered agencies, including Defense, the intelligence community, FAA, NASA, and the National Archives. Cite the order’s definitions section so agencies can harmonize. (National Archives) - Inventory and indexing

Order each agency to finish a UAP records inventory in ninety days and provide a public index of releasable records with rolling release dates and a clear status for items still under review. Require referrals to other equity holders under section 3.6 when needed. (National Archives) - Collection at the Archives

Direct the Archivist to host a UAP Records Collection portal and to publish a running release log. Require agencies to transmit releasable records in open formats on a sixty day cadence. This mirrors best practice in prior topical releases. (Legal Information Institute) - Guide rewrite and training

In thirty days, order each agency to issue new classification guide paragraphs that prevent over classification of UAP topics. ISOO can audit these guides under existing authority. (National Archives) - Appeals and oversight

Direct ISCAP to prioritize UAP MDR appeals and publish decisions quickly. This already occurs in other areas and drives consistent government wide outcomes. (National Archives) - Statutory carve outs

Affirm that nothing in the order supersedes the Atomic Energy Act, the National Security Act, or protection of covert identities. Make DOE and DOD concurrence the rule for any nuclear associated information. Quote Section 6.2 of E.O. 13526 to avoid doubt. (National Archives)

Speculated Timeline of Disclosure

First 30 days

Issue the order, designate a senior coordinator at the National Security Council, publish agency points of contact, and post the indexing template at the Archives. Agencies begin inventories and guide rewrites. ISOO and ISCAP announce UAP queues. This is realistic because the scaffolding already exists in E.O. 13526 and its directive. (National Archives)

Days 31 to 90

Agencies deliver initial indexes and first tranches of releasable records. AARO publishes an unclassified overview of holdings and scheduled releases across the community. The Archives posts a UAP Collection page with batch releases and status logs. (AARO)

Days 91 to 180

The second wave of releases includes more complex materials such as sanitized sensor video, incident reconstructions, and historical program documents, with redactions tied to explicit harm statements or statutory citations. ISCAP begins to publish UAP appeal decisions that set markers for future processing. (National Archives)

Beyond 180 days

Agencies continue rolling releases, and the White House reports publicly on what remains withheld and why, broken down by exemption or statutory category. If statutory barriers block high value public understanding, the Administration sends Congress a legislative proposal identifying precisely what changes would be required to permit fuller release. (eCFR)

Impact Analysis

Public trust and policy feedback

A schedule driven, rules based disclosure plan signals that UAP transparency is a governance problem, not a culture war. FOIA backlogs shrink for this topic when MDR and appeals are coordinated under the order. The Archives gains a single place for the public and researchers to find authenticated records. (National Archives)

Security balance

By using the existing harm tests and statutory carve outs, an order can lift the veil on facts that carry low risk while protecting technical collection. The explicit deference to the Atomic Energy Act and covert identity statutes prevents a false collision between transparency and the law. (National Archives)

Institutional learning

ISCAP decisions stack up into a usable common law of UAP declassification. Agency guides tighten over time. That improves future performance even after the order has run its course. (National Archives)

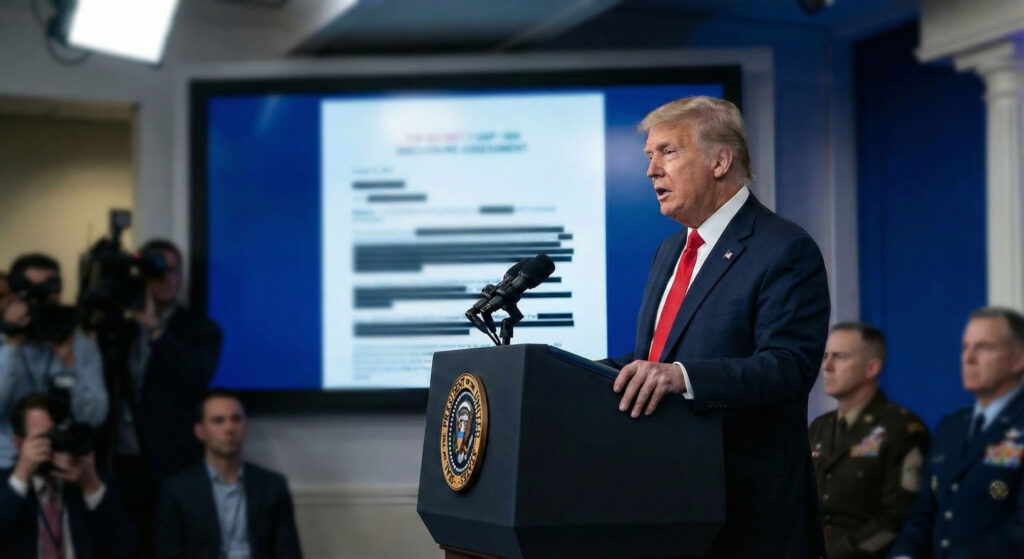

Why the current President matters

As of November 2025, the current President is Donald J. Trump. Any decision to issue a UAP transparency order rests with him and his advisors. The White House can, in one signature, initiate the blueprint outlined above and set expectations for the entire executive branch. The authority to do so does not depend on new legislation, although Congress can expand or constrain the scope through statute. (Wikipedia)

Bottom Line

A President who wants UAP transparency has a strong tool kit ready to use. An executive order can quickly align agencies, set deadlines, and compel public releases for materials controlled under the order driven classification system.

That tool kit stops at statutes. Anything captured by the Atomic Energy Act, the protection of covert identities, or similar laws is outside the reach of an order and must be handled under those regimes or brought to Congress for legislative change.

The fastest path to meaningful public understanding is therefore a precision order that leans into existing declassification machinery, makes smart use of ISCAP and MDR, and draws bright statutory lines.

References

Executive Order 13526, Classified National Security Information, National Archives ISOO page. (National Archives)

ISOO Implementing Directive, 32 C.F.R. part 2001. (National Archives)

Mandatory Declassification Review guidance. (National Archives)

Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel overview and decisions. (National Archives)

United States v. Zubaydah, 595 U.S. ___ (2022), state secrets in modern practice. (Legal Information Institute)

FOIA statute, 5 U.S.C. § 552. (Legal Information Institute)

DoD special access program notice requirements, 10 U.S.C. § 119. (Legal Information Institute)

ODNI legal reference for National Security Act authorities. (Director of National Intelligence)

AARO home page for current public reporting. (AARO)

Congressional UAP records collection proposals in the 118th Congress. (Congress.gov)

White House and reference confirmation of the current President. (The White House)

National Archives, Information Security Oversight Office. Executive Order 13526, Classified National Security Information, overview and PDF; Implementing Directive 32 C.F.R. part 2001; ISOO guidance on MDR and marking; ISCAP overview and decisions. (National Archives)

Supreme Court of the United States, Department of the Navy v. Egan, 484 U.S. 518 (1988). (Legal Information Institute)

Supreme Court of the United States, United States v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1 (1953); and United States v. Zubaydah, 595 U.S. ___ (2022). (Legal Information Institute)

Department of Energy, Statutes, Regulations, and Directives for the Classification Program; 10 C.F.R. part 1045 Nuclear Classification and Declassification. (The Department of Energy’s Energy.gov)

Law Library Institute, Cornell. 5 U.S.C. § 552, Freedom of Information Act; 10 U.S.C. § 119, Special access programs; 50 U.S.C. § 3121, Intelligence Identities Protection. (Legal Information Institute)

Claims Taxonomy

Verified

- Executive Order 13526 establishes the current uniform system for classifying, safeguarding, and declassifying national security information. It is implemented by 32 C.F.R. part 2001. (National Archives)

- The Supreme Court in Department of the Navy v. Egan recognized the President’s primary authority to control access to national security information unless Congress has provided otherwise. (Legal Information Institute)

- E.O. 13526 Section 6.2 states that nothing in the order supersedes requirements under the Atomic Energy Act or the National Security Act. (National Archives)

- The Atomic Energy Act and 10 C.F.R. part 1045 govern the classification and declassification of Restricted Data and Formerly Restricted Data. (The Department of Energy’s Energy.gov)

- The Intelligence Identities Protection Act protects certain covert identities by statute. (Legal Information Institute)

- DoD special access programs have congressional notice requirements when classification changes or declassification is planned. (Legal Information Institute)

Probable

- A tailored UAP transparency order would significantly accelerate public access to historical incident files and sanitized media that are classified only under the executive order, while leaving statutory categories largely untouched. (Inference from the authorities above.)

Disputed

- Claims that a President can unilaterally declassify any nuclear related UAP material by executive order alone. The order’s own text and DOE regulations indicate otherwise. (National Archives)

Legend

- Narratives that a single signature could instantly reveal all answers about UAP. Real world law and process do not support that expectation.

Misidentification

- Statements that FOIA by itself forces release of all UAP material. FOIA contains explicit exemptions for properly classified information and for information protected by other statutes. (Legal Information Institute)

Speculation Labels

Hypothesis

A UAP focused executive order that sets a ninety-day inventory, a one hundred eighty day first wave of releases, and directs ISCAP to prioritize UAP appeals would produce a visible public collection inside six months with minimal litigation, because it rides on the existing E.O. 13526 and 32 C.F.R. part 2001 architecture.

Researcher opinion

The most valuable near term releases will be historical incident files, sanitized video and tracks, and program level summaries that show how the government has organized its UAP work. These can be disclosed with low risk when classification guides are rewritten to avoid blanket treatment of non sensitive context.

Witness interpretation

Many observers expect “everything” to be released at once. That is not how the law works. Statutory carve outs and harm tests will shape what the public sees. A clear calendar with plain language explanations will help align expectations with reality.

SEO Keywords

UAP executive order, presidential declassification power, Executive Order 13526, UAP records collection, ISCAP appeals, mandatory declassification review, Atomic Energy Act Restricted Data, ODNI sources and methods, AARO transparency, FOIA UAP requests, special access programs, state secrets privilege, National Archives UAP collection, UAP disclosure timeline, UAP implications for national security.