J. Allen Hynek stands as one of the most consequential figures in the modern history of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena. At once a classically trained astronomer and a relentless advocate for systematic inquiry, he bridged two worlds that rarely spoke to each other. He brought to the UAP problem a scholar’s ability to sort and name, an investigator’s instinct for fieldwork, and a teacher’s gift for explaining complex matters to a curious public. His journey from early Air Force consultant to the architect of a scientific program for civilian research reshaped how generations would think about lights in the sky, craft without obvious propulsion, and the many human stories attached to both. He did not resolve the mystery. He made it harder to dismiss. (Britannica)

Early life, education, and the making of a scientist

Josef Allen Hynek was born in Chicago on May 1, 1910, to parents who had immigrated from what is now the Czech Republic. A bright student with an early passion for astronomy, he completed a Bachelor of Science at the University of Chicago in 1931, then earned his PhD in astrophysics at the university’s Yerkes Observatory in 1935. His early work focused on stellar astrophysics, and he began an academic career at Ohio State University in 1936, rising through the ranks as a teacher and researcher. The habits of careful observation, skeptical analysis, and patient method were formed in these years. They would later define his approach to anomalous reports in the sky.

During the Second World War he served as a civilian scientist at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, working on proximity fuzes. After the war he returned to Ohio State, directing the McMillin Observatory and becoming full professor and an assistant dean by 1950. These are not incidental biographical notes. Hynek’s later authority in the UAP domain came from being a working astronomer who understood both the discipline and the instruments, and who had earned the respect of colleagues long before anyone associated his name with flying saucers.

Sputnik, Moonwatch, and a vantage point on the sky

In the mid 1950s, Hynek moved to the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, where he served as associate director of the optical satellite tracking program during the International Geophysical Year. He helped design and deploy a world network for tracking earth satellites, including the famed Baker Nunn camera stations, and was a public face of the scientific response to the launch of Sputnik in October 1957. Those days gave him a global network of observers and a deep familiarity with how the sky looks when seen through lenses, film, and the human eye. It is no accident that the scientist who helped coordinate Moonwatch would later insist that eyewitness testimony, when carefully collected and tested against physical constraints, could become data.

In 1959 he accepted the chairmanship of the astronomy department at Northwestern University. There he spearheaded innovations in image orthicon television detectors for telescopes and built out observatory capabilities in New Mexico and on campus. He was a builder and institution maker in academic astronomy. The skills translated. When he later created an independent center for UAP research, he did so as someone who had already organized laboratories, instruments, and teams.

Air Force consultant and the long road to Blue Book

Hynek’s name entered the UAP story in 1948, when the Air Force, responding to a wave of postwar sightings, formed Project Sign and sought scientific consultants. He was an obvious choice. At Ohio State, he was close to Wright Patterson Air Force Base, and as an astronomer he could quickly evaluate whether a reported object might be a star, planet, meteor, balloon, aircraft, or something misperceived. He consulted for Sign, then for its successor Project Grudge, and finally for Project Blue Book, which ran from 1952 until 1969. He remained the project’s scientific consultant for most of its life, sifting through reports, visiting cases in the field, and writing technical analyses. The popular story that he began as a debunker is half true. He did start from a skeptical posture, confident that most reports could be resolved with careful work. Yet over years of investigation, he found that a residue remained that resisted conventional identification and that the consistency of some reports, especially from trained observers, merited attention rather than ridicule. (Britannica)

Hynek had a front row seat to how the official program succeeded at procedural tasks and how it fell short. He complained about inadequate resourcing, insufficient technical support for instrumented cases, and an institutional tendency to move quickly to mundane explanations without exhausting alternatives. In July 1968 he joined other scientists in a House Science and Astronautics Committee symposium on the subject, where he urged a more vigorous scientific investigation of the phenomenon and cautioned against the presumption that every report could be waved away. His carefully argued statement in the congressional record stands as one of the clearest expressions of his mature view. (GovInfo)

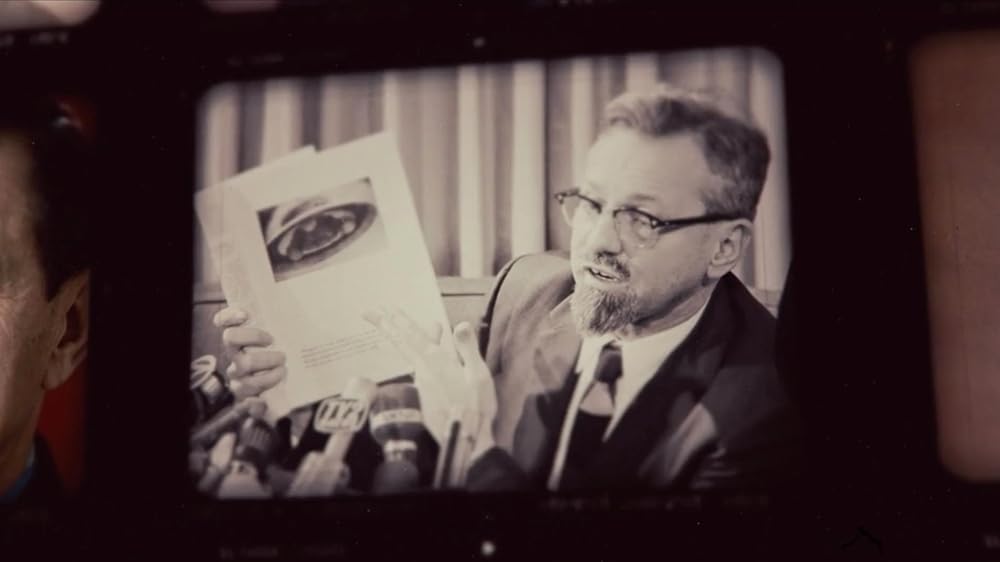

The Michigan storm and a phrase that would haunt him

In March 1966, a wave of reports in southeastern Michigan culminated in two tense nights around Dexter and Hillsdale. Hynek was sent to investigate. After long days in the field, he offered “marsh gas” or swamp gas as a plausible explanation for a subset of the sightings, with the caveat that the term did not apply across the board. The press seized upon the two words. The nuance disappeared. The phrase became a national punchline, and the episode helped push Rep. Gerald Ford of Michigan to call for congressional hearings, which occurred on April 5, 1966. The incident was a turning point for Hynek, who later said the reaction taught him how not to communicate about a complex and emotionally charged subject. It also hardened his conviction that the phenomenon deserved more than casual dismissal. (fordlibrarymuseum.gov)

Hynek eventually put that lesson into a principle. “Ridicule is not a part of the scientific method,” he wrote, and the public should not be taught that it is. The admonition became a touchstone of his later work and an implicit rebuke to colleagues who treated civilian observers as fools. The line appears in his book The UFO Experience, and the broader argument in that text shows how he sought to move discussion from the language of derision to the language of categories, evidence, and repeatable procedures.

The UFO Experience and the architecture of Close Encounters

Published in 1972, The UFO Experience gave the field a backbone. Hynek separated distant cases into three families, Nocturnal Lights, Daylight Discs, and Radar Visual, then defined the now famous Close Encounters of the First, Second, and Third Kinds for events within about 500 feet, where misidentification becomes less likely and physical effects sometimes appear. The scheme did not explain any given sighting, but it allowed researchers to talk to each other without confusion and to build case catalogs that would support comparative analysis. Two things made his classification powerful. It respected the limits of what could be concluded from each kind of report, and it highlighted where the data were richest, namely the close range encounters that came with trace evidence, instrumented readings, or multiple observers. Hynek did not claim that a Close Encounter proved the presence of a craft from another world. He made a more modest and more profound claim. Close Encounters asked questions that ordinary explanations could not easily answer.

Popular culture absorbed this language. Steven Spielberg borrowed Hynek’s Third Kind for the title of his 1977 film. Hynek served as a technical adviser and made a brief cameo near the end, a bearded astronomer stepping forward, pipe in hand, to witness the arrival. His presence was more than a stunt. It was a signature. The film told a story in which the human desire to know meets a phenomenon that refuses easy classification. Hynek had spent decades living that story. In interviews around the premiere he repeated a simple clarification. He had never seen a UAP himself, he said, but he had seen enough consistent testimony and perplexing data to know that science ought to take the matter seriously. (Roger Ebert)

Unfinished business after Condon

Between 1966 and 1968 the Air Force funded a study at the University of Colorado under physicist Edward Condon. Its final report concluded that the study of UAP was unlikely to advance science and that most reports related to ordinary phenomena. The National Academy of Sciences endorsed the general thrust of the findings, and the Air Force closed Project Blue Book in 1969. Hynek disagreed on both scientific and organizational grounds. He argued that the report was uneven, that its introduction did not reflect the content of many unresolved cases in its own appendices, and that the subject required long term instrumented fieldwork rather than episodic case analysis. He did not ask colleagues to accept dramatic conclusions. He asked them not to turn their backs on persistent anomalies.

Building institutions for civilian research

In 1973, Hynek founded the Center for UFO Studies in the Chicago area, initially in Evanston. CUFOS became a research clearinghouse and archive, home to the International UFO Reporter and later to the Journal of UFO Studies, and a place where investigators compared notes across disciplines. Hynek served as scientific director and recruited an informal network of scientists and scholars that sociologist and data scientist Jacques Vallée, his close collaborator, famously called the Invisible College. Before he died, Hynek asked Mark Rodeghier to succeed him, and CUFOS continues today, preserving case files and supporting investigations. The creation of CUFOS marked a quiet revolution. For the first time in the United States, a sustained, private, science oriented institution would steward UAP data outside government channels.

Fieldwork and cases that moved the needle

Hynek’s Air Force years and his later CUFOS period both brought him to case sites. Two deserve special mention because they illustrate how his thinking evolved. In April 1964, Socorro, New Mexico police officer Lonnie Zamora reported a close range sighting of an oval object on landing struts and two small figures in white coveralls, followed by a rapid departure and scorched brush. Hynek found the physical traces persuasive and the witness credible. Blue Book left the case as unknown, and years of attempts to retrofit it to local pranks or test devices have not produced a consensus explanation. For Hynek, Socorro signaled that some reports could not be answered with a stock list of planets, balloons, or planes.

Two years later, in April 1966, officers in Portage County, Ohio chased a luminous object for miles across state lines. The case inspired the dramatic police pursuit scene in Spielberg’s film, and it provoked debate in every direction. Hynek read the reports and interviewed the officers, then confronted the same dilemma that marks so many solid cases. Distance estimates, angular motion, and atmospheric conditions could be argued either way. The event lacked the trace evidence that elevates a case to the second kind. Yet the witnesses were trained and insistent that what they saw was not Venus or a conventional aircraft. Hynek’s pragmatic response was the same he would give for the rest of his career. Some percentage of good cases resist solution and must be cataloged, not erased. The important thing is to collect enough of them, with enough precision, to permit pattern recognition and testable hypotheses.

Public advocacy, international forum, and the wider circle

Hynek was not content to argue within a closed circle. He testified at the 1968 House symposium and later addressed the United Nations Special Political Committee in November 1978 with Vallée and the French engineer Claude Poher. Their aim was modest and practical, to create a mechanism for international coordination and data sharing. The language of that statement is classic Hynek, neither sensational nor dismissive, and it points to the same middle path he walked for two decades, a call for steady collection, fair analysis, and institutional memory.

Partnerships, hypotheses, and intellectual courage

Hynek’s collaboration with Jacques Vallée shaped late twentieth century UAP thinking. Vallée pushed for a data centric approach that considered both physical and cultural dimensions, while Hynek insisted that even the strangest reports be examined with the same care as an astronomical light curve. Together they resisted simplistic answers. Hynek did not settle for the idea that all UAP must be visitors from other star systems, nor did he settle for the idea that misidentification explains the core residue. He left open a range of possibilities, including phenomena that might require new physics or a reality that overlaps ours in ways not yet understood. In this he was both conservative and adventurous. He did not leap to conclusions, but he refused to fence inquiry within the expectations of existing theory. (wired.com)

Books and a voice that reached beyond the lab

The UFO Experience laid down the conceptual architecture. The Edge of Reality, co authored with Vallée in 1975, extended the conversation about method and meaning. The Hynek UFO Report in 1977 summarized case material and his perspective on government handling of the problem, while Night Siege, published with Philip Imbrogno and Bob Pratt shortly after Hynek’s death, modeled how a long duration regional wave could be investigated. These books mattered because they were written by a scientist with academic credentials and field experience, and because he aimed them at readers who wanted more than sensational claims or casual debunks. (si.edu)

Northwestern years, Hollywood cameo, and the weight of controversy

Northwestern was Hynek’s academic home from 1960 to his retirement in 1978. Administrators valued his leadership in building a modern department, even as some faculty grew uncomfortable with his prominence as the nation’s most recognizable UAP scientist. He made his cameo in Close Encounters in 1977, a wink to those who followed his work and a signal that the language he forged had entered the culture. The tension he navigated at Northwestern mirrors the tension he asked the country to navigate. A serious academic could also be serious about a problem that many found uncomfortable. Hynek paid a reputational price for that stance. He also gained the respect of a public that had long suspected the subject deserved more than laughter. (Roger Ebert)

Death and legacy

J. Allen Hynek died of a brain tumor on April 27, 1986, in Scottsdale, Arizona. He was seventy five. Obituaries emphasized the paradox of his career, the pipe smoking professor who tried to bring order to a subject that confounded the institutions around him. The institutional legacy he left was CUFOS, still preserving files and training investigators. The intellectual legacy he left was a way to talk about the phenomenon with categories, not caricatures. The cultural legacy he left was a vocabulary that countless documentaries, journalists, and scholars still use. Above all, he left a challenge. When faced with consistent reports that do not map to known phenomena, science must fold those reports into its processes rather than laugh them away. (latimes.com)

Hynek’s impact on the UAP subject

Three enduring contributions define his impact.

First, he put structure where there had been confusion. The Close Encounters framework still organizes databases and research programs. It gives investigators a common language and a stable taxonomy, which is the first step in any maturing science. Just as astronomers classify stars or galaxies before answering deeper questions, Hynek taught UAP scholars to classify encounters before arguing about origins.

Second, he insisted that the best cases come from the intersection of credible witnesses and physical effects. He did not dismiss testimony by pilots or police officers as a matter of course, and he demanded ground checks, magnetometer sweeps when available, and careful documentation of burns, mechanical interference, and animal reactions. His method privileged data that might be checked after the fact, and it encouraged long term projects such as regional surveillance and multi sensor campaigns. Even in the era of modern military reporting, where infrared imagery and radar fusion have returned the topic to the center of policy debates, researchers continue to discover that Hynek’s emphasis on multi modality was prophetic.

Third, he created a place for the work to live. The closing of Blue Book might have ended serious inquiry in the United States for a generation. Hynek’s creation of CUFOS, with its library, periodicals, and case files, ensured continuity. It also trained a cadre of investigators who would carry forward the insistence that even a small fraction of good cases challenge current knowledge and therefore justify continued investigation.

A balanced but heterodox scientist

It is easy to mistake Hynek’s caution for indecision. He was measured because he was a scientist trained to separate what is known from what is suspected. He was heterodox not because he chased every wild claim but because he refused to pretend that anomalies vanish when one averts one’s gaze. He did not teach that most sightings are misidentifications and nothing more. He taught that once you have worked through the misidentifications, the residue is large enough, consistent enough, and often physical enough to warrant real science. That stance is neither sensational nor trivial. It is the seed from which a true research program grows.

Today, researchers revisit old case files with new techniques, scour declassified archives for instrument data, and design targeted field experiments. Each of these threads looks back to Hynek. He connected the realism of an astronomer who measured stars with the patience of a field investigator who knocks on doors. He gave this topic a vocabulary and a home, and in doing so, he gave it a future.

Timeline summary

1910: Born in Chicago

1931: BS in astronomy, University of Chicago

1935: PhD in astrophysics, Yerkes Observatory

1936 to early 1950s: Faculty at Ohio State, rising to full professor and assistant dean

1942 to 1946: Civilian scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

1948 onward: Scientific consultant to Project Sign, then Grudge, then Blue Book

1956 to 1960: Associate director of the Smithsonian optical satellite tracking program, a leader in Moonwatch

1960 to 1978: Chair and professor at Northwestern University

1966: Michigan wave, swamp gas controversy, House hearing

1968: Testimony at House Science and Astronautics symposium

1969: Project Blue Book closes

1972: Publishes The UFO Experience

1973: Founds the Center for UFO Studies

1975: Co-authors The Edge of Reality with Jacques Vallée

1977: Publishes The Hynek UFO Report, serves as technical adviser to Close Encounters of the Third Kind and makes a cameo

1978: Addresses United Nations Special Political Committee with Vallée and Poher

1986: Dies in Scottsdale, Arizona

References for key statements in the text include institutional biographies, archives, and Hynek’s own works. For his positions at Northwestern and biographical detail, see the university’s archival entry. For his Air Force consulting and the closure of Blue Book, see the National Archives material. For the Michigan hearings, see the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library press releases. For his classification system and its subsequent cultural impact, see The UFO Experience and contemporary overviews. For the United Nations appearance, see the prepared statement and UN documentation. (National Archives)

Selected bibliography

- Hynek, J. Allen. The UFO Experience: A Scientific Inquiry. Chicago, IL: Henry Regnery, 1972. [Smithsonian Libraries catalog entry confirms publication details.] (si.edu)

- Hynek, J. Allen. The Hynek UFO Report. Chicago, IL: CUFOS, 1977. [Full text available via archival scans.]

- Hynek, J. Allen, Philip J. Imbrogno, and Bob Pratt. Night Siege: The Hudson Valley UFO Sightings. New York, NY: Ballantine, 1987.

- Hynek, J. Allen, and Jacques Vallée. The Edge of Reality: A Progress Report on Unidentified Flying Objects. Chicago, IL: Henry Regnery, 1975.

- United States House of Representatives, Committee on Science and Astronautics. Symposium on Unidentified Flying Objects, July 29, 1968. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968. (GovInfo)

- Vallée, Jacques F., J. Allen Hynek, and Claude Poher. “Statement about the UFO Phenomenon before the Special Political Committee of the United Nations,” New York, November 27, 1978.

References

Books and reports

Hynek, J. Allen. The UFO Experience: A Scientific Inquiry. Chicago, IL: Henry Regnery, 1972. (si.edu)

Hynek, J. Allen. The Hynek UFO Report. Chicago, IL: CUFOS, 1977.

Hynek, J. Allen; Jacques Vallée. The Edge of Reality: A Progress Report on Unidentified Flying Objects. Chicago, IL: Henry Regnery, 1975.

Hynek, J. Allen; Philip J. Imbrogno; Bob Pratt. Night Siege: The Hudson Valley UFO Sightings. New York, NY: Ballantine, 1987.

United States Congress, House Committee on Science and Astronautics. Symposium on Unidentified Flying Objects, July 29, 1968. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968. (GovInfo)

Condon, Edward U. et al. Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado, 1968. See summaries and analyses for context.

Vallée, Jacques F.; J. Allen Hynek; Claude Poher. Statement before the UN Special Political Committee, November 27, 1978.

Institutional and archival sources

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “J. Allen Hynek.” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “J. Allen Hynek Center for UFO Studies.” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

National Archives. “Do Records Show Proof of UFOs.” (National Archives)

OSI, U.S. Air Force. “Project Blue Book Part 1.” (osi.af.mil)

Northwestern University Libraries. “Hynek, J. Allen (Joseph Allen), 1910–1986,” Archival and Manuscript Collections.

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. “Ford Press Releases – UFO, 1966.” (fordlibrarymuseum.gov)

Smithsonian Institution Archives blog. “Right Places at the Right Time.”

Smithsonian Magazine. “Sputnik Spawned a Moonwatch Madness.”

Atlas Obscura. “Amateur Astronomers Have Always Been Great at Finding Satellites.”

CUFOS and related publications

CUFOS. “About Us.”

CUFOS. Journal of UFO Studies documents.

CUFOS. International UFO Reporter issues.

CUFOS. Board and leadership pages for Mark Rodeghier.

News and features

History.com. Greg Daugherty, “Meet J. Allen Hynek, the Astronomer Who First Classified UFO ‘Close Encounters’.” (history.com)

WTTW Chicago. “How a Controversial Chicago Astronomer Influenced ‘Close Encounters’.” (WTTW News)

Roger Ebert.com. “Top secret: Steven Spielberg on the brink of the ‘Close Encounters’ premiere.” (Roger Ebert)

Los Angeles Times. “J. Allen Hynek Dies; Led AF Investigation of UFOs.” (latimes.com)

Daily Northwestern. “Remembering NU professor J. Allen Hynek’s UFO research.”

Case specific references

“Lonnie Zamora incident,” background on Blue Book status and subsequent debates.

“Famous 86 mile UFO chase in 1966,” coverage of the Portage County event.

Quotations and definitions

Hynek, “Ridicule is not a part of the scientific method,” sourced to The UFO Experience.

Overview of Hynek’s classification system and its adoption.

SEO keywords

J Allen Hynek, Center for UFO Studies, CUFOS, Close Encounters, Hynek classification, Project Blue Book, Project Sign, Project Grudge, Michigan swamp gas, Socorro case, Portage County chase, Jacques Vallee, United Nations UFO statement, satellite tracking program, Operation Moonwatch, Northwestern University, UAP history, UAP research, Hynek UFO Report, The UFO Experience