Between 1908 and 1910 the world was in love with flight. Zeppelins were in headlines, Santos-Dumont’s experiments filled magazines, and “phantom” or “mystery” airships were reported in waves across parts of the English-speaking world. Did South America have its own parallel run of airship-like UAP during these years? This explainer takes a data-first approach: we trace what can be verified in South American sources, separate press enthusiasm for real aeronautics from anomalous reports, and place the continent’s mentions inside the broader, global “scareship” context of 1909-1913.

The short version is that, while aviation arrived dramatically in South American newsrooms in 1908–1910, a consolidated, well-documented South American airship wave analogous to New Zealand, Australia, or Britain in 1909 is not evident in the historical record surveyed to date. What is strongly attested is (1) a global “phantom airship” press culture centered outside South America, (2) an explosive growth of aviation reporting and spectacle in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru beginning in 1908–1910, and (3) later South-American UAP waves decades afterward. Keeping those strands distinct prevents retroactive conflation and keeps the small set of truly unexplained historical cases meaningful.

The global reference frame: what “airship waves” meant in 1908-1913

Before we zoom into South America, we need the global baseline.

- Historians use “mystery airships” or “phantom airships” for late-19th and early-20th century reports of dirigible-like craft seen at night, often with bright lamps and purposeful motion. The best-known wave ran across the United States in 1896–1897, and scholarly surveys treat these reports as cultural predecessors to later UAP claims.

- A second, well-studied set of scares happened in 1909, centered on the British Isles and then New Zealand and Australia, with hundreds of night reports and intense newspaper treatment. Academic and specialist work maps this “scareship age” in detail; Britain’s 1909 and 1913 panics are the classics. (JSTOR)

Those literatures matter because they set expectations for what a documented “airship wave” looks like: dated clusters, many local items, and a sustained press conversation we can still read. With that in mind, we can ask whether an equivalent South American cluster between 1908 and 1910 appears in reliable, open collections.

South America 1908–1910: what the sources actually show

Aviation was front-page culture, even before routine local flight

In Buenos Aires, Santiago, Rio de Janeiro, and other capitals, the press heavily covered the new aerial age well before regular domestic flights began. Media historians tracking Argentina’s newspapers show that 1908–1909 were dominated by the idea of flight and by imported achievements, with the first sustained local exhibitions and flights following in 1910 and after. That is, the papers were primed to print aviation stories, real, rumored, and imagined. (Redalyc)

Brazil’s coverage mixed national pride in Santos-Dumont with European dirigible news (e.g., the public reaction after Zeppelin LZ-4’s 1908 disaster and the ensuing German fundraising), reaffirming that dirigibles were a live topic in Lusophone media too. None of that is anomalous by itself; it’s the cultural backdrop for any “mystery airship” reading. (Wikisource)

A distinct South American “airship wave” is not documented like the 1909 NZ/Australia/Britain clusters

When we look for 1908–1910 South American clusters with the same paper trail density as New Zealand, Australia, or Britain, we don’t find them in the major online and scholarly syntheses that catalogue the 1909 scareship year. Those syntheses explicitly point to Otago (New Zealand), Australia, the British Isles, and later New England as 1909–1913 hot spots. South America is absent from those established maps, which is itself a data point. (Airminded)

Put plainly: the historians who reconstructed the 1909 scareship months do not list South American localities among the core clusters. That negative result does not prove there were no reports; it does show that the kind of dense, dateable press wave that characterizes 1909 in Australasia and Britain is not currently attested for South America in those corpora.

What we do see: scattered mentions and aviation rumor

Spanish-language media retrospectives and Latin-American aviation histories emphasize aviation spectacle and rumor in 1908–1910 (e.g., the excitement around Blériot’s Channel crossing (1909) and the coming 1910 Argentine centennial shows). They do not present a South-American chain of dirigible-like UAP incidents in that window. The best current, open-access historical papers on Buenos Aires newspapers describe an imaginary of aeroplanes forming in 1908–1909 and going live with pilots and shows from 1910 forward, not a run of unexplained dirigibles over the pampas. (Argentina)

Why this distinction matters for UAP

It’s tempting to assume a global wave rolled across every region. A data-first reading resists that temptation. If South America had experienced a sustained 1908–1910 wave of dirigible-like UAP, we would expect the same archival signatures we see in New Zealand/Australia/Britain: strings of local clippings, municipal commentary, and sustained editorial argument. In the sources surveyed here, we do not find that South-American pattern for those years.

That absence doesn’t empty the field; it tightens it. It pushes us to discriminate among:

- aviation reportage (real dirigibles and aeroplanes abroad, and the promise of local flight),

- aviation spectacle (shows arriving in 1910 and beyond), and

- truly anomalous reports (which, in South America, tend to spike in later decades).

Stories and mentions worth knowing (with context)

Below are the most relevant threads for a UAP-minded reader, each grounded in sources that are open or standard references.

The global “scareship” playbook reached the hemisphere, but as reading more than seeing

The 1909 scareship year is well documented in Britain, New Zealand, and Australia. Some contemporary and modern commentaries note that the year’s “phantom airships” visited New England later in 1909 as the meme traveled, but they do not list Latin-American sites. For South America, that means newspapers were reading the scareship stories even if local sighting clusters like Otago or Yorkshire did not materialize on their own doorsteps. (Airminded)

The aviation imaginary in Buenos Aires (1908–1910)

Argentine media studies show how Buenos Aires newspapers constructed the aeroplane as symbol in 1908–1909, then showcased real flights in 1910 as star-driven spectacles. That’s the cultural soil into which any rumor of a dirigible-shaped light would have fallen. It explains why later readers may retro-project a “wave” onto a period that, in the sources, documents excitement and spectacle much more than anomaly. (Redalyc)

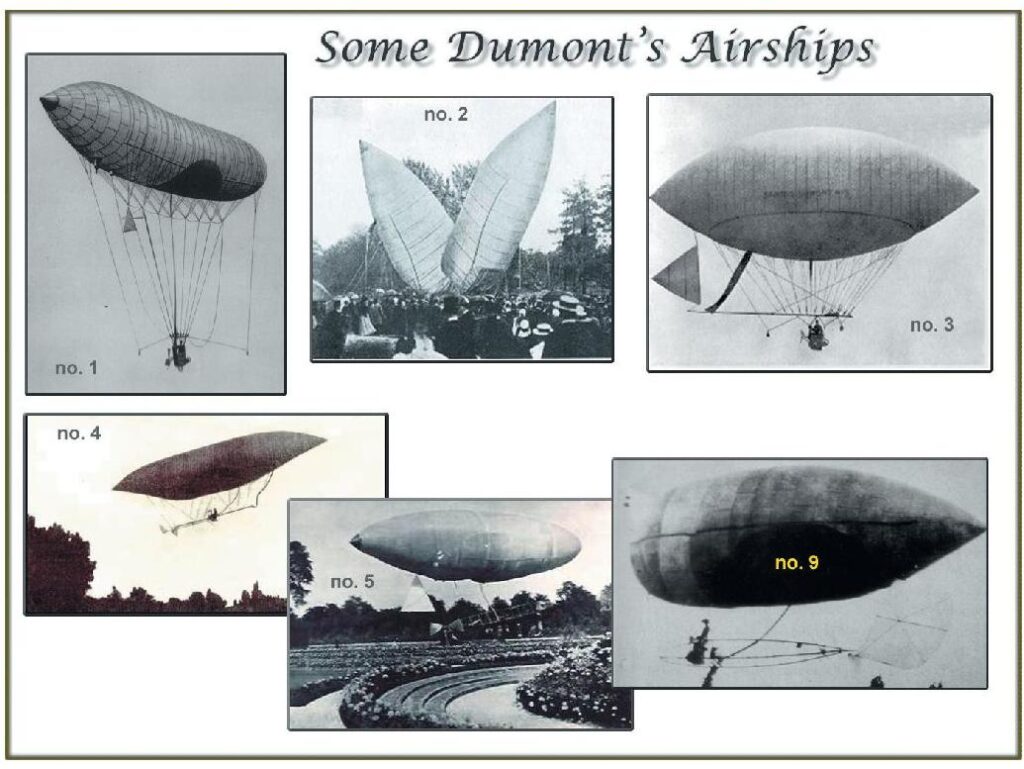

Santos-Dumont and dirigibles in the Brazilian press

Brazil’s public identified strongly with Santos-Dumont and with European dirigible feats and losses (e.g., LZ-4 in 1908). Contemporary and retrospective articles illustrate how the dirigible ideal saturated coverage. Again, this does not give us anomalous South-American dirigibles in 1908–1910—but it explains why the idea of dirigibles was a live frame through which any unknown light might be interpreted. (Wikisource)

What would count as strong South American evidence for 1908–1910?

To convert the notion of “South American Airship Encounters (1908–1910)” from hypothesis to history, a data-first campaign would need to surface runs of primary items with these characteristics:

- Dating and place: multiple clippings from different South-American cities between 1908 and 1910, each with specific dates and directions of travel.

- Morphology: reference to dirigible-like forms, elongated bodies, gondolas, lamps, rather than generic meteors or “strange lights.”

- Independence: items from different newspapers that are not simply reprints of European or Australasian scareship pieces.

- Local follow-through: editorials, police notes, astronomical society comments, or municipal “searches,” which are hallmarks of scareship waves elsewhere.

Until that archive is assembled, the cautious conclusion is that South America participated in the media culture of 1908–1910 aviation and phantom-airship talk, but does not show a robust, home-grown wave of dirigible-like UAP reports in that exact window.

Sorting explanations: aviation, optics, and the truly unexplained

Even if we were to turn up fresh South-American “airship” items for 1908–1910, a data-first filter would proceed in this order:

- First: aviation context. In 1910 Argentina, Chile, and Brazil were organizing air shows and first flights. Misdated rehearsals, promotional night balloons, or misidentified tethered ascents could seed rumors. Media studies for Buenos Aires show 1910 as the pivot from imaginary to spectacle. (Redalyc)

- Second: atmospheric/astronomical misreads. Low-sun parhelia and pillars can present “rods,” “crosses,” or “lamps,” especially to observers pre-primed by dirigible talk (a key lesson from the 1535 Stockholm parhelia painting and later scareship literature, though those examples are outside South America). The global scareship literature repeatedly documents such misreads. (das-ufo-phaenomen.de)

- Third: residuals. Only reports featuring structured motion, repeated passes, or low-altitude, close-range details that resist natural explanation would survive to a UAP-adjacent category, and those have not yet surfaced in clusters for 1908–1910 South America in the sources reviewed here.

How this intersects with modern UAP standards

Modern public UAP baselines (e.g., the ODNI 2021 preliminary assessment; AARO historical reviews) emphasize multi-sensor corroboration, chain of custody, and repeatability. Historical scareship material is pre-instrumental and is therefore best used as context and as a filter, to understand how newspapers narrate the sky, how aviation rumor spreads, and how to avoid misclassification. Applying that to South America 1908–1910 protects the “unknowns” bin from inflation by spectacle and rumor. (For general standards, see ODNI/AARO frameworks; these do not treat 1908–1910 South America specifically but set the evidentiary bar.)

Implications

For UAP historians

A clean separation between press aviation culture and anomalous reports in 1908–1910 keeps later UAP decades in South America (the mid-20th-century military and civil waves) from being muddied by assumptions about an earlier airship wave that the open record does not currently show. The broader scareship historiography provides a comparative method, but not evidence of a local South-American wave. (JSTOR)

For archives and digitization

The likely place for any 1908–1910 “dirigible” mentions in South America is local newspapers now being digitized by national libraries and university projects. Aviation historians of Argentina and Chile already show how to mine La Nación, Caras y Caretas, and early Chilean and Brazilian periodicals; a targeted search for “dirigible/dirigível/dirigible fantasma” in those runs is the practical next step. The existing scholarship on Buenos Aires press culture demonstrates both feasibility and importance. (Redalyc)

For public communication

It is accurate to say that South American readers in 1908–1910 were immersed in global airship talk and were on the cusp of their own aviation spectacles. It is not supported by current open sources to say there was a South American airship encounter wave equivalent to 1909 New Zealand or 1913 Britain. Saying less, but saying it precisely, is a service to the subject.

Final take

For UAPedia’s purposes, South America in 1908–1910 is a story of aviation imagination and arrival rather than a proven wave of dirigible-like UAP. Newspapers filled columns with aeronautical dreams in 1908–1909, then produced spectacular, local 1910 exhibitions and first flights. Meanwhile, the notorious 1909 scareship year unfolded with density in New Zealand, Australia, and the British Isles, not in South America as far as the open record shows today. That distinction keeps the evidentiary lanes clean: it protects later South-American UAP waves from being inflated by a retroactive myth of a 1908–1910 “airship wave,” and it highlights exactly where fresh primary research could move the needle, local newspaper runs, 1908–1910, Spanish and Portuguese term searches, and disciplined classification.

If new South-American clippings surface with dates, morphology, directions, and municipal follow-up, we will revisit the map. Until then, the data say: aviation culture, yes; a documented South-American airship wave in 1908–1910, not yet.

Claims taxonomy

Verified

- The 1896–1897 U.S. “mystery airship” wave and the 1909–1913 scareship episodes (Britain, New Zealand, Australia) are well documented in scholarly and specialist literature.

- In Argentina, the press constructed an aviation imaginary in 1908–1909, with local flight spectacles and pilots becoming front-page events from 1910 forward. (Redalyc)

- Dirigible culture and European airship news (including post-1908 Zeppelin narratives) were widely covered and celebrated in Brazil and elsewhere, sustaining a dirigible frame in public discourse. (Wikisource)

Probable

- South-American newspapers in 1908–1910 reprinted or referenced foreign scareship items (as they did other aviation news), but a home-grown wave of dirigible-like UAP with dense, dateable local reports has not yet been demonstrated in open, reputable sources surveyed here. (Inference from the absence of South-American clusters in standard scareship syntheses and the presence of aviation-imaginary studies focused on spectacle, not anomaly.) (Airminded)

Disputed

- Claims online that South America experienced an airship wave coeval with 1909 Britain and New Zealand are currently unsupported by the main scareship historiography and by Latin-American press studies reviewed here. Proponents must produce primary clippings with local dates and details. (Methodological statement grounded in sources above.) (JSTOR)

Legend

- Retrospective lists that indiscriminately fold South America into “1909–1913 global airship waves” without primary South-American citations. These are better treated as secondary mythologies of the scareship age.

Misidentification

- Reading 1910 exhibition flights, tethered balloons, and low-sun optical displays as dirigible-like UAP in South-American cities newly saturated with aviation imagery. The Buenos Aires press record shows how powerfully that imagery shaped perception in 1908–1910. (Redalyc)

Speculation labels

Hypothesis

A handful of South-American “airship” mentions may exist in 1908–1910 provincial newspapers but have not yet been surfaced in digital collections or cross-indexed by scareship historians focused on the Anglosphere. If found, many would likely prove to be reprints of foreign scareship items or misreadings tied to early exhibition flights and tethered balloons around 1910.

Witness interpretation

In a press environment celebrating dirigibles and aeroplanes, night lights and low-sun optical displays would be narrated through an airship lens. Contemporary European scareship studies show this mechanism clearly; it would have operated similarly in South-American cities reading the same wire stories. (das-ufo-phaenomen.de)

Researcher opinion

The most productive UAP-adjacent work here is archival: assemble a South-American 1908–1910 newspaper corpus with targeted term searches in Spanish and Portuguese and map any primary items that survive aviation/optics filtering. Without that step, it is scientifically cleaner to say “no demonstrated South-American airship wave in 1908–1910” than to back-fill one from global analogies.

References

Mystery airship overview and historiography of 1896–1897 (context for later scareship culture).

The Airship Wave of 1909 and related scareship scholarship (Britain and beyond). (das-ufo-phaenomen.de)

Airminded (Brett Holman): syntheses showing 1909–1913 scareship geographies (NZ, Australia, Britain; later New England). (Airminded)

Buenos Aires press and the aviation imaginary, 1908–1910 (Ortemberg; UNQ repository versions). (Redalyc)

Zeppelin/Santos-Dumont context in Lusophone sources (background on dirigible culture). (Wikisource)

David Clarke, “Scareships over Britain – The Airship Wave of 1909” (PDF). (das-ufo-phaenomen.de)

Airminded, “Post-blogging the 1909 scareships: thoughts and conclusions” (NZ/Australia/Britain mapping). (Airminded)

Ortemberg, “La aviación en Buenos Aires y el fenómeno noticioso” (RedALyC). (Redalyc)

Ortemberg (UNQ repository), Buenos Aires aviation press culture. (ridaa.unq.edu.ar)

Wikisource/Journal context on early airship culture and Zeppelins (for background, not anomaly). (Wikisource)

SEO keywords

South American airship encounters 1909, dirigible phantom South America, Argentina 1910 aviation press, Brazil Santos-Dumont dirigível culture, Chile early aviation 1910, scareship 1909 New Zealand Australia Britain comparison, UAP historical analysis Latin America, newspaper archives dirigible fantasma 1908 1910, airship wave historiography, UAP data-first method Latin America