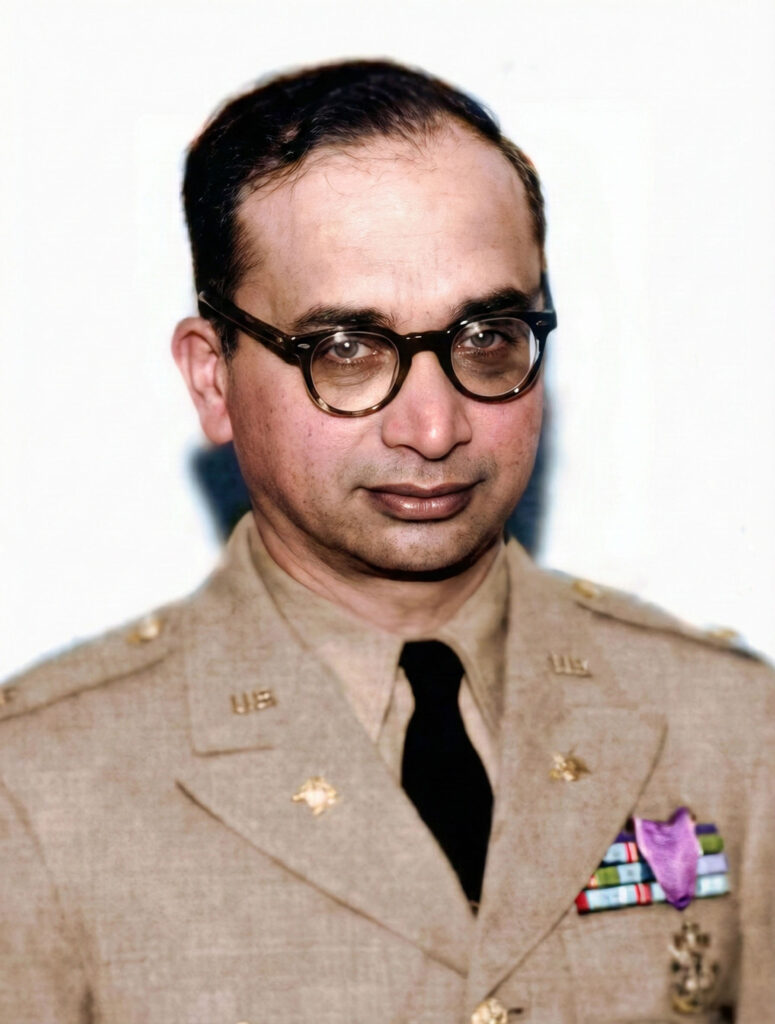

Philip J. Corso was a U.S. Army intelligence officer whose late‑career claims about recovered non‑human technology made him a central figure in the modern UAP narrative. In his 1997 book The Day After Roswell, coauthored with William J. Birnes, Corso said he helped introduce artifacts from the 1947 Roswell crash into U.S. defense research during the early 1960s, seeding breakthroughs in integrated circuits, fiber optics, lasers, and night‑vision systems. The book turned Corso into a widely discussed voice, and it also triggered strong critical pushback and official counter‑narratives. (Simon & Schuster)

Early life and military career

Corso was born in California, Pennsylvania, on 22 May 1915, and served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1963, reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel. (theblackvault.com) His publisher’s biography states that he spent four years on President Eisenhower’s National Security Council staff and, in 1961, became chief of the Army Research and Development “Foreign Technology” desk under Lt. Gen. Arthur G. Trudeau. (Simon & Schuster)

After leaving active duty, Corso worked on Capitol Hill. Public records and contemporaneous reporting show him testifying and advocating on POW/MIA questions in the 1990s, and he provided testimony to the Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs in 1992. (TIME) Corso died in Florida on 16 July 1998 at age 83. (Openminds.tv)

Entry into the historical record

Corso stepped into the UAP conversation publicly with The Day After Roswell (Pocket Books). The book presented two headline claims. First, that he personally saw a non‑human body in a shipping container at Fort Riley in 1947. Second, that he later “seeded” Roswell‑derived components to U.S. labs and defense contractors while at the Pentagon, which he said catalyzed several Cold War‑era technologies. (Internet Archive)

The book was promoted as a New York Times bestseller by the publisher. It initially carried a foreword from Sen. Strom Thurmond, who was then embarrassed by the book’s UAP content and publicly distanced himself from it soon after publication. (Simon & Schuster) A Los Angeles Times report also documented litigation noise around the book’s rollout that same year. (Los Angeles Times)

What the documentary record can confirm

Service and access. There is open‑source support for Corso’s Army career and Pentagon R&D work under Trudeau. The publisher biography is explicit on those points. (Simon & Schuster) Corso’s appearances before Congress on POW/MIA issues are also on record. (C-SPAN)

NSC staff status. Corso and his publisher described him as an Eisenhower‑era NSC staffer. Skeptical researchers later cited an archivist at the Eisenhower Library who said there is no documentary evidence he was NSC staff. That archivist’s statement is reported second‑hand in Kevin Randle’s research notes. UAPedia flags government archives as important yet not infallible, so this remains a contested biographical detail. (Simon & Schuster)

Roswell and recovered materials. The U.S. Air Force responded in the 1990s to renewed Roswell interest with two official reports. The 1994 report attributed the debris to Project Mogul. The 1997 “Case Closed” report addressed “bodies” accounts as likely stemming from later anthropomorphic‑dummy tests and unrelated mishaps. These reports reject the idea of non‑human craft or bodies at Roswell. UAPedia’s editorial policy accepts that such government narratives must be considered and compared with witness‑driven accounts, not treated as the final word. (DAF History)

Technology chronology checks. Corso’s narrative links Roswell artifacts to postwar breakthroughs. The documented timelines show independent, well‑attributed origins for several items he listed.

- Integrated circuit, Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments in 1958, with Robert Noyce’s monolithic IC patent following in 1959. (NobelPrize.org)

- Laser, first demonstrated by Theodore Maiman at Hughes Research Laboratories in 1960. (HRL)

- Fiber optics, the term and early image‑transmission breakthroughs were popularized by Narinder Singh Kapany by 1960, building on earlier optics work. (Wikipedia)

- Kevlar, discovered at DuPont by Stephanie Kwolek in 1965. (Science History Institute)

- Night‑vision devices, fielded in military form before 1947, with German systems under development by the mid‑1930s and in combat tests by the early 1940s. (Encyclopedia.pub)

These timelines do not rule out the possibility of classified stimulus or accelerants. They do show that each technology has a documented lineage in mainstream research communities.

Independent assessments of the book. Skeptical analyses, including a 1998 Skeptical Inquirer review by Brad Sparks and coverage from the Skeptics UFO Newsletter archive, cataloged factual and chronological issues in the text and questioned several military‑technical assertions. (Center for Inquiry)

Corso’s lasting impact

Regardless of whether one accepts his account, Corso helped mainstream the idea that the United States quietly introduced non‑human technology into Cold War R&D pipelines. His story reframed Roswell from a recovered‑craft narrative into an enduring “technology seeding” thesis. That frame influenced later whistleblowing, FOIA campaigns, and congressional interest in crash‑retrieval and reverse‑engineering programs, and it provides an interpretive backdrop for today’s official reviews. (Government Executive)

UAPedia records government positions in line with our editorial policy on official sources and continues to track primary materials that could clarify what, if anything, Corso handled inside Army R&D. See our policy note for how we weigh official statements alongside non‑government testimony and documents.

Timeline

- 1915 – Born in California, Pennsylvania. (theblackvault.com)

- 1942–1963 – U.S. Army service in intelligence roles during World War II and Korea, retiring as lieutenant colonel. (Simon & Schuster)

- 1953–1957 – Publisher biography states service on Eisenhower’s NSC staff. Status disputed by later archivist comment reported by researchers. (Simon & Schuster)

- 1961–1963 – Chief of the Army R&D “Foreign Technology” desk under Lt. Gen. Arthur G. Trudeau, per publisher biography. (Simon & Schuster)

- 1992 – Testifies on POW/MIA issues before the Senate Select Committee. (C-SPAN)

- 1997 – Publishes The Day After Roswell. Thurmond foreword controversy follows. (Simon & Schuster)

- 1998 – Dies in Florida at age 83. (Openminds.tv)

Primary works and key media

- Corso, P. J., with Birnes, W. J. The Day After Roswell. Pocket Books, 1997. (Internet Archive)

- C‑SPAN video excerpt of Corso’s 1992 Senate testimony on POW/MIA issues. (C-SPAN)

References

Corso, P. J., & Birnes, W. J. (1997). The day after Roswell. Pocket Books. https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Day-After-Roswell/William-J-Birnes/9781501172007?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Government Executive. (1997, June 4). The senator and the UFOs. https://www.govexec.com/federal-news/1997/06/the-senator-and-the-ufos/3223/?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

U.S. Air Force. (1994). Report of Air Force Research Regarding the “Roswell Incident”. https://www.dafhistory.af.mil/Portals/16/documents/AFD-101201-038.pdf?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

U.S. Air Force. (1997). The Roswell report: Case closed. https://media.defense.gov/2010/Oct/27/2001330219/-1/-1/0/AFD-101027-030.pdf?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

All‑domain Anomaly Resolution Office. (2024, March). Historical Record Report, Vol. 1. https://www.aaro.mil/Portals/136/PDFs/AARO_Historical_Record_Report_Vol_1_2024.pdf?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

C‑SPAN. (1992). Col. Philip Corso, Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs (clip). https://www.c-span.org/clip/senate-committee/user-clip-col-philip-corso/4990890?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Nobel Prize. (2000). Jack S. Kilby – Nobel Lecture. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2000/kilby/lecture/?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Computer History Museum. (n.d.). Practical monolithic integrated circuit concept patented. https://www.computerhistory.org/siliconengine/practical-monolithic-integrated-circuit-concept-patented/?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

HRL Laboratories. (n.d.). About the laser. https://www.hrl.com/about/laser?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Science History Institute. (n.d.). Stephanie L. Kwolek. https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific-biographies/stephanie-l-kwolek/?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

MDPI Encyclopedia. (2022). Night‑vision device. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/29146?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Sparks, B. (1998). Philip Corso’s Roswellmania. Skeptical Inquirer, 22(2), 52–55. https://cdn.centerforinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/1998/03/22164921/p52.pdf?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Open Minds. (2010, July 16). The day Col. Corso died. https://openminds.tv/the-day-col-corso-died/?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Simon & Schuster. (n.d.). Philip Corso, author page. https://www.simonandschuster.com/authors/Philip-Corso/1246221?utm_source=https://uapedia.ai

Editorial Note

Corso’s biography is unusually polarizing inside the UAP record. His service and access are well supported. His most consequential claims remain uncorroborated in official archives, and the prevailing government position today is that there is no verified reverse‑engineering program. UAPedia documents both sides, prioritizes primary sources and firsthand testimony, and continues to track records that could clarify Corso’s role in Army R&D and in any handling of anomalous materials.

SEO keywords: Philip J. Corso, The Day After Roswell, Roswell crash, Army Research and Development, Foreign Technology desk, reverse engineered UAP technology, Strom Thurmond foreword, AARO Historical Record Report, integrated circuit origin, fiber optics history, laser invention, Kevlar discovery.