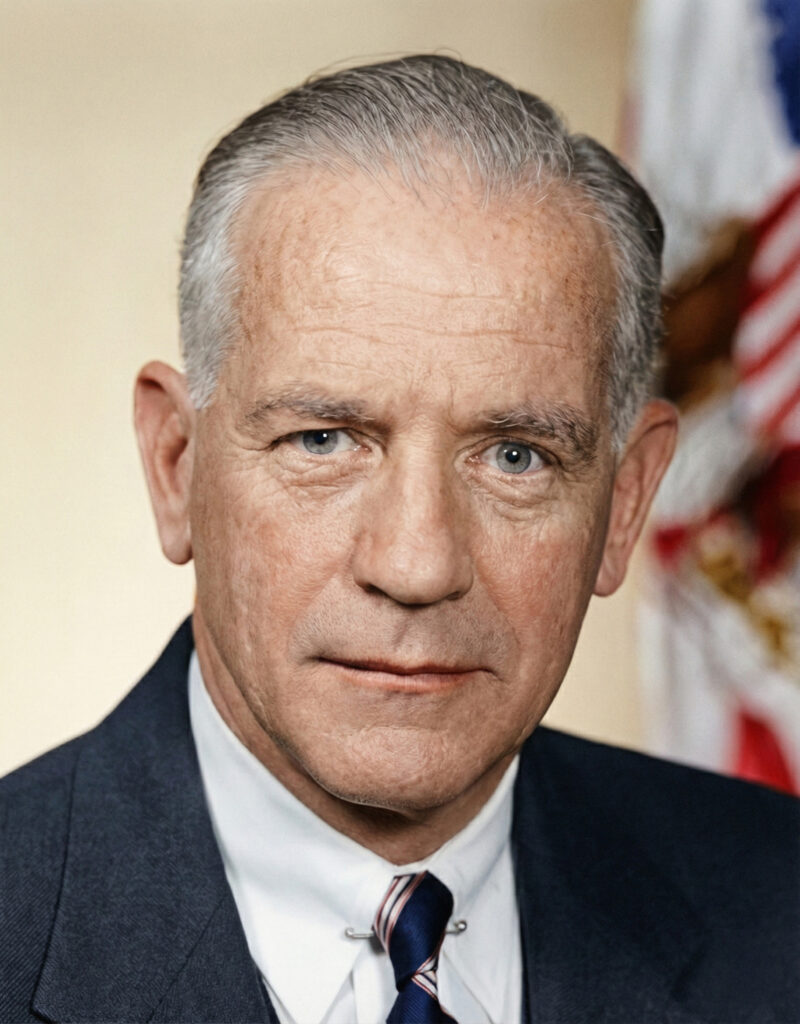

Gordon Gray’s public résumé reads like a primer on how national security policy was built in mid-century America. Publisher of the Winston-Salem Journal, Yale-trained lawyer, Secretary of the Army under Truman, first director of the Psychological Strategy Board, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission Personnel Security Board that judged J. Robert Oppenheimer, Director of the Office of Defense Mobilization, and finally National Security Advisor to President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

He later served for years on the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. This proximity to the nerve center of Cold War secrecy made him an ideal character for later claims about a small interagency group created to manage recovered non-human technology.

His name appears on the “Eisenhower Briefing Document” as a member of “Majestic 12,” a purported committee formed in 1947 to control the UAP problem.

The UAP Gray lives in debates over MJ-12, in podcasts and books that argue either for a hidden recovery effort or for a crafted fiction built on plausibility. To understand why his name still animates ufology, one must grasp both portraits. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

Early life, education, and ascent

Gordon Gray was born in Baltimore on May 30, 1909, and grew up in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in a family tied to R. J. Reynolds.

After an undergraduate education and Yale Law School, he practiced law and returned home to manage the family’s media holdings. By the late 1940s his blend of legal training, publishing influence, and political connections had carried him into national service.

Truman appointed Gray Assistant Secretary of the Army in 1947, then Secretary of the Army in 1949. In 1950 he briefly served as a Special Assistant to the President.

In 1951 he became the first director of the newly created Psychological Strategy Board, which coordinated non-military information and influence policy across the government during the Korean War. These posts honed his aptitude for interagency management and classified decision making. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

Gray left the Pentagon to become president of the University of North Carolina system in 1950, then returned to Washington in 1955 as Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs.

Eisenhower named him Director of the Office of Defense Mobilization in 1957, and in 1958 Gray became National Security Advisor, following Robert Cutler. He earned the Medal of Freedom in 1961 and later served many years on the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board under successive administrations.

The Oppenheimer hearing and a reputation for decisive secrecy

Gray’s most controversial public assignment came in 1954 when he chaired the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) Personnel Security Board that reviewed the government’s case against J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The Board concluded, two to one, that Oppenheimer’s clearance should be revoked. Gray voted with the majority.

The AEC later affirmed the revocation. Whether one judges that decision as an overreach of Cold War suspicion or as a security-driven necessity, the hearing cemented Gray’s public identity as a steady steward of the security state at a moment when science, politics, and secrecy collided. (Wikipedia)

The “Gray Board” episode still shadows his name. For UAP historians, it signals the kind of compartmental discipline and political will that a White House would demand if a truly extraordinary recovery or analysis program ever existed. That is one reason MJ-12 list-makers found Gray’s name irresistible. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

The official UAP landscape during Gray’s prime

Gray’s high-level service overlapped with the government’s formal UAP efforts.

After the 1947 wave, the Air Force created Project SIGN in 1948, replaced it with Project GRUDGE in 1949, and established Project BLUE BOOK in 1952.By the time BLUE BOOK closed in 1969, the Air Force had logged 12,618 cases. The program’s final summaries listed 701 as “unidentified” by its own standards and asserted that the remainder posed no direct national security threat and revealed no confirmed technologies beyond contemporary science.

These numbers and conclusions provide the institutional context for Gray’s tenure as Eisenhower’s National Security Advisor and later as a senior adviser to presidents. (National Archives)

The Robertson Panel and the policy tone of the 1950s

In January 1953, the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence convened the Scientific Advisory Panel on Unidentified Flying Objects (UFOs), known popularly as the Robertson Panel.

The declassified “Durant report” summarizes its briefings and conclusions.

The panel found no evidence of a direct threat in the reports reviewed and recommended a public education program to reduce spurious reports and a more disciplined field-investigation protocol.

Although Gray did not sit on this panel, the panel’s advice harmonized with the broader national security style he helped implement: filter and manage anomalous reporting while protecting core defense systems and political stability. (CIA)

The MJ-12 claim: what the papers say and what the archivists say

What the Eisenhower Briefing Document claims

In the mid-1980s, an undeveloped roll of film mailed anonymously to a television producer yielded a document titled “Operation Majestic-12,” a purported “Top Secret/Eyes Only” briefing dated 16 November 1952 for President-elect Eisenhower.

The roster lists twelve “designated members,” including Admiral Roscoe Hillenkoetter, Vannevar Bush, Detlev Bronk, Donald Menzel, Nathan Twining, Hoyt Vandenberg, Sidney Souers, Jerome Hunsaker, Robert Montague, and Gordon Gray. The document sketches a narrative of a 1947 crash in New Mexico, alleged retrievals, biological analyses, and liaison arrangements with Air Force UAP projects.

If authentic, it would place Gray inside a tight circle managing sensitive recoveries and policy. (Internet Archive)

The federal custodians’ verdict

The National Archives maintains a dedicated portal that describes extensive negative searches for corroboration and lists anomalies in the so-called “Cutler/Twining” memo, long cited as an archival anchor for MJ-12.

The anomalies include missing Top Secret register numbers and a scheduling conflict showing Robert Cutler overseas on the day the memo was supposedly written. In 1995, the Government Accountability Office reported to Congress that executive-branch agencies found no evidence that MJ-12 materials were legitimate government records.

These judgments are the most authoritative public positions available. (FBI)

Why Gray’s name stuck anyway

MJ-12’s cast list is plausibly curated. A real crash-retrieval oversight body would likely have included the CIA director (or former director), senior Air Force leadership, top scientific administrators, and a White House-level coordinator.

Gray fits that last slot. As National Security Advisor, former Secretary of the Army, director of the Psychological Strategy Board, and future PFIAB member, he had the clearances, the interagency influence, and the habit of discretion that such a body would demand. Plausibility, however, is not proof.

UAPedia therefore treats the Eisenhower Briefing Document as an artifact of the debate rather than as a verified historical record, and balances it against the FBI, GAO, and NARA positions.

What Gray himself said about UAP

A search of Gray’s published papers and oral histories reveals no on-the-record statements by him endorsing or elaborating extraordinary UAP hypotheses.

His writing and memoranda focus on national security organization, psychological strategy, and security-clearance issues.

There is no authenticated public claim by Gray about crash recoveries, non-human technology, or the nature of unexplained sightings. In the open record, his UAP footprint is created by others who invoke his name. (Truman Library)

Influence on ufology

The “plausible casting” effect. Many researchers describe MJ-12 as persuasive storytelling because its personnel choices feel right to anyone who understands 1947–1952. Gray’s presence on that roster is a prime example.

He personifies the White House coordinator who could knit military, intelligence, and scientific voices together. That narrative logic helped MJ-12 lodge in public and media consciousness, from television specials to podcasts, whether cited as truth or as an influential hoax. (Internet Archive)

The tone-setting of 1950s policy. Gray’s real work shaped the apparatus that later handled UAP reporting. The Psychological Strategy Board’s creation and the later National Security Council process under Eisenhower helped normalize controlled communication about ambiguous threats.

The CIA-convened Robertson Panel’s advice dovetailed with this posture. That policy DNA influenced Air Force practice through BLUE BOOK’s life and into later decades. (Truman Library)

A foil for contemporary reassessments. Today, podcasts and investigators often revisit MJ-12 to discuss whether a hidden recovery effort could have existed even if the specific documents were forgeries.

In that reassessment, Gray’s career is used to model how a real mechanism might have been staffed and protected. Skeptical voices point to the FBI and NARA findings and to document-forensics work by researchers such as Philip J. Klass.

Proponents point to books like Stanton Friedman’s Top Secret/MAJIC and to interviews or films that treat MJ-12 as a gateway into a larger hidden history. Either way, Gray is a touchstone in the argument. (Skeptical Inquirer)

Claims attributed to Gray, and what the record supports

Because Gray did not publicly claim anything about UAP, the only “claims” that tie him to the phenomenon appear in the MJ-12 corpus.

The Eisenhower Briefing Document’s narrative places him on a committee overseeing biological analysis, recovery policy, and liaison with Air Force UAP projects. Those descriptions are assertions that have not been authenticated.

Archival sources that can be named and checked identify no such committee in their official holdings, and federal agencies advise that the MJ-12 papers are not genuine government documents. Responsible historiography treats the MJ-12 text as a claim about Gray, not as evidence from Gray. (Internet Archive)

Other controversies that shape how ufology sees Gray

The Oppenheimer decision. As chair of the AEC Personnel Security Board, Gray voted to revoke Oppenheimer’s clearance. That vote has remained a lightning rod for scientists and historians. In the ufology world, the episode often appears as a parable about the costs of crossing entrenched security structures.

Gray’s own Board letter acknowledged Oppenheimer’s loyalty, yet concluded that patterns in his conduct were incompatible with clearance. The lasting debate about whether justice or fear carried the day colors how Gray is remembered in other secrecy-adjacent stories. (Wikipedia)

Director of the Psychological Strategy Board. Gray’s year at PSB put him at the center of an enterprise dedicated to coordinated, often classified influence operations. UAP historians use this to explain how the government might manage public narratives about anomalies.

Primary sources at the Truman Library confirm Gray was the Board’s first director and that PSB’s mission was to coordinate psychological strategy across agencies. (Truman Library)

Civil-military policy while Secretary of the Army. Gray’s tenure overlapped with the implementation phase of desegregation after Truman’s 1948 order. Archival commentary shows he approved specific regulations while the Army struggled through reform and mixed institutional resistance. For some social historians this is the most important controversy of his career.

It underscores his role as an agent of difficult policy in contentious times, which is part of why later narratives cast him as a reliable manager of sensitive problems. (AUSA)

Why Gray’s name belongs in any history of UAP policy

Even setting MJ-12 aside, Gray’s life matters for UAP history because it shows how the United States built the machinery to handle ambiguous, potentially destabilizing information.

He operationalized the NSC process, linked policy to communications strategy, and made interagency coordination habitual. When the Air Force struggled with the flood of sightings in the 1950s, it did so inside a policy culture Gray helped shape. The Robertson Panel reflected that culture.

BLUE BOOK’s public stance did as well. Today’s AARO review cites decades of data and cultural problems that flowed from those early choices. Gray deserves attention because his biography is a guide to the architecture of secrecy and communication that defined UAP governance. (CIA)

Selected timeline

- 1909. Born in Baltimore, Maryland.

- 1947–1949. Assistant Secretary of the Army. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

- 1949–1950. Secretary of the Army. (Wikipedia)

- 1950. Special Assistant to President Truman. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

- 1951–1952. First Director, Psychological Strategy Board. (Truman Library)

- 1954. Chairs AEC Personnel Security Board in the Oppenheimer case. (Wikipedia)

- 1955–1957. Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs. (Wikipedia)

- 1957–1958. Director, Office of Defense Mobilization. (Wikipedia)

- 1958–1961. National Security Advisor to Eisenhower. Medal of Freedom in 1961. (Wikipedia)

- 1961–1977. Member, President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

- 1982. Dies in Washington, D.C.

- 1984–1988. MJ-12 documents surface naming Gray as a member; FBI, National Archives, and later GAO reject them as authentic government records. (FBI)

Books, podcasts, and researchers who shaped the Gray–MJ-12 conversation

UAPedia emphasizes triaging sources by evidentiary weight while noting how cultural narratives form. For the MJ-12 story around Gray, three categories matter.

Books making the case for MJ-12’s reality.

Stanton T. Friedman’s Top Secret/MAJIC is the foundational pro-MJ-12 book. Friedman argues for the documents’ authenticity and uses insider interviews to build a narrative around the roster that includes Gray. Even critics acknowledge the book’s influence in mainstreaming the list. (Internet Archive)

Researchers and writers challenging MJ-12.

Philip J. Klass, a veteran aerospace journalist, led early document forensics efforts that identified date-format anomalies, signature issues, and the Cutler travel conflict. Klass published analyses in Skeptical Inquirer and later papers, arguing the documents could not withstand scrutiny.

These critiques undergird the federal custodians’ skepticism and remain essential reading. (Skeptical Inquirer)

Podcasts that revisit the terrain for new audiences.

Brian Dunning’s Skeptoid episode “The Secret History of Majestic 12” walks listeners through the claims, the personalities, and the forensics.

John Greenewald’s The Black Vault Radio site aggregates FBI files and frequently revisits MJ-12 claims and new “releases” with caution. Contemporary UAP podcasts such as Need to Know and WEAPONIZED occasionally reference MJ-12 while exploring broader secrecy questions and whistleblower claims.

Together these shows keep Gray’s name in the current conversation and expose new audiences to both sides of the archival debate. (Skeptoid)

Balanced conclusions

Gordon Gray’s verified biography is formidable. He helped design how the U.S. government coordinates sensitive policy, managed information campaigns, chaired the most famous security-clearance hearing in scientific history, and served as Eisenhower’s chief national security aide.

That is the record. The UAP narrative adds a layer of fascination.

The Eisenhower Briefing Document placed Gray in a clandestine committee charged with extraordinary technical and biological matters.

Why does his name endure in ufology anyway?

Because if such a group had existed, one would expect to find a Gordon Gray at the table. His career checks every box: White House proximity, interagency authority, comfort with compartments, and a reputation for shepherding hard decisions. The plausibility that made him a prime suspect on an MJ-12 list also explains why the story will not die.

For researchers, the lesson is twofold. First, separate what the archives say from what a document claims. Second, pay attention to the architecture of secrecy. Gray’s life shows how a government might handle a genuine unknown. It also shows how, in the absence of verified documents, stories will gravitate to the people who could have held the keys.

UAPedia’s heterodox stance holds that a durable remainder of UAP reports has resisted conventional explanation, even as official reviews emphasize data gaps and the absence of verified non-human technology programs. In that ambiguity, Gordon Gray remains a symbol: of competence and discretion for some, of managed narratives for others. Until more decisive declassifications emerge, his place in UAP history is best understood as a product of both his authentic power in the national security system and the enduring pull of a single, disputed set of pages that made him one of twelve. (National Archives)

References

All-domain Anomaly Resolution Office. (2024). Report on the historical record of U.S. government involvement with UAP, Vol. 1. U.S. Department of Defense. https://www.archives.gov/research/topics/uaps (National Archives)

Britannica. (n.d.). Gordon Gray. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gordon-Gray (Encyclopedia Britannica)

CIA. (1953). Report of meetings of Scientific Advisory Panel on Unidentified Flying Objects (Robertson Panel/Durant report). https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/document/cia-rdp79b00752a000300100010-4 (CIA)

Eisenhower Presidential Library. (n.d.). Gordon Gray: Papers, 1946–1976. https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/research/finding-aids/gray-gordon and PDF finding aid: https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/finding-aids/pdf/gray-gordon-papers.pdf (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

FBI. (n.d.). Majestic 12 (The Vault). https://vault.fbi.gov/Majestic%2012 and PDF archive mirror via The Black Vault: https://documents.theblackvault.com/documents/fbifiles/majestic.pdf (FBI)

Friedman, S. T. (1997). Top Secret/MAJIC. Marlowe & Co. Archive copy: https://archive.org/details/topsecretmajic0000frie (Internet Archive)

Klass, P. J. (1988). The MJ-12 crashed-saucer documents. Skeptical Inquirer. https://skepticalinquirer.org/1988/01/the-mj-12-crashed-saucer-documents/ (Skeptical Inquirer)

Klass, P. J. (2000). The new bogus Majestic-12 documents. Skeptical Inquirer. https://centerforinquiry.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/2000/05/22164853/p44.pdf (Center for Inquiry)

National Archives and Records Administration. (2025). UFO and UAP-related records [includes MJ-12 reference notes and how to research]. https://www.archives.gov/research/topics/uaps (National Archives)

Skeptoid. Dunning, B. (2016). The Secret History of Majestic 12 [Podcast episode #528]. https://skeptoid.com/episodes/528 (Skeptoid)

The Black Vault. (n.d.). Majestic-12 document archive and podcast show notes. https://www.theblackvault.com/documentarchive/majestic-12/ and https://www.theblackvault.com/documentarchive/the-black-vault-radio-show-notes-episode-breakdown/ (The Black Vault)

Truman Presidential Library. (n.d.). Portrait of Gordon Gray, Secretary of the Army [Photo records]. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/2003-100 and https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/97-1823

Truman Presidential Library. (n.d.). Psychological Strategy Board files. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/truman-papers/harry-s-truman-papers-staff-member-and-office-files-psychological-strategy (Truman Library)

U.S. Air Force. (n.d.). Unidentified flying objects and Air Force Project BLUE BOOK [Fact sheet; historical summary]. https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/104590/unidentified-flying-objects-and-air-force-project-blue-book/ (see NARA UAP portal for current access routes) (National Archives)

Archive.org reproduction. (n.d.). Eisenhower Briefing Document: Operation Majestic-12 [disputed]. https://ia800500.us.archive.org/35/items/majestic-12-documents-for-majic-eyes-only/Eisenhower%20Briefing%20Document_text.pdf (Internet Archive)

NCpedia. (n.d.). Gray, Gordon [biographical entry]. https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/gray-gordon

AUSA. (2014). Truman Learned Army Culture Change Isn’t Easy [context on Gray’s 1950 Army regulation during desegregation]. https://www.ausa.org/articles/truman-learned-army-culture-change-isn%E2%80%99t-easy (AUSA)

Britannica. (n.d.). J. Robert Oppenheimer security hearing [context on the Gray Board]. https://www.britannica.com/event/J-Robert-Oppenheimer-security-hearing (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Blum, H. (1990). Out There: The Government’s Secret Quest for Extraterrestrials. Simon & Schuster. Catalog entry: https://www.amazon.com/Out-There-Governments-Secret-Extraterrestrials/dp/0671662600 (Amazon)

Need to Know podcast. (2025). Selected episodes referencing MJ-12 claims in broader secrecy discussions. Example: “Watch the Skies.” https://open.spotify.com/episode/7JNXi5FjNbApDrceCFDItt (Spotify)

WEAPONIZED podcast. (2023–2025). Knapp & Corbell on secrecy, whistleblowers, and historical claims including MJ-12. https://www.weaponizedpodcast.com/episodes-1/episode-number-12 and show feed: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/weaponized-with-jeremy-corbell-george-knapp/id1664299388 (WEAPONIZED)

SEO keywords

Gordon Gray biography UAP, Gordon Gray Majestic 12, MJ-12 Eisenhower Briefing Document Gray, Psychological Strategy Board and UAP, Oppenheimer security hearing Gray Board, National Security Advisor 1958 UAP context, Project BLUE BOOK statistics, AARO 2024 UAP history, Skeptoid Majestic 12 episode, Black Vault MJ-12 documents, Stanton Friedman Top Secret/MAJIC, Philip Klass MJ-12 critique.