Vannevar Bush did not chase lights in the sky. He built the institutions, tools, and habits of mind that made systematic observation of the sky, sea, and space possible at scale. As the wartime head of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development, the founding chair of the National Defense Research Committee, president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, a co‑founder of Raytheon, and the intellectual force behind the National Science Foundation, Bush engineered the research state that still shapes how we detect, record, and analyze unidentified anomalous phenomena. He also imagined the “memex,” a personal knowledge machine whose spirit lives on in today’s hyperlinked archives and digital UAP catalogs. Any honest accounting of UAP history must therefore start with the scaffolding he erected for sensing and for knowledge itself. (Britannica, n.d.; The Atlantic, 1945; NSF, 2020s).

(NARA – Beth Gore Credit: Harris & Ewing)

Early life and education

Vannevar Bush was born on March 11, 1890, in Everett, Massachusetts, the son of a Universalist minister. He grew up in nearby Chelsea and graduated from Tufts College in 1913 with both a Bachelor of Science and a Master of Science, a dual arrangement then possible at Tufts. After short stints at General Electric and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, he pursued advanced study and received a doctorate in electrical engineering in 1916 under a joint MIT–Harvard arrangement, working with the eminent electrical engineer Dugald C. Jackson. These early experiences fused practical craft, mathematical rigor, and institutional savvy. (Britannica, n.d.; NAS Biographical Memoir). (Britannica)

Building machines that could “think” with calculus

In 1919 Bush joined the MIT electrical engineering faculty and set out to mechanize the most stubborn work of engineers: the solution of differential equations. By 1930–1931 he and colleagues Harold L. Hazen, Samuel H. Caldwell, and others built the “differential analyzer,” a room‑sized analog computer that solved complex equations by interconnecting mechanical integrators through shafts, gears, and torque amplifiers. The machine rapidly became a magnet for talent, including graduate assistant Claude Shannon, who tended the analyzer and then wrote his epochal 1937 master’s thesis showing how Boolean algebra could underpin digital logic. Bush’s analog vision and Shannon’s digital leap formed a complementary dyad that quietly set the technical substrate for modern data processing, including the signal handling pipelines behind radar, infrared, and multi‑sensor UAP recording. (MIT Museum; Computer History Museum; MIT News; Britannica). (MIT Museum)

Entrepreneurial streak: Co‑founding Raytheon

Bush was never only an academic. In 1922 he joined Laurence K. Marshall and Charles G. Smith to found the American Appliance Company in Cambridge. The firm pivoted quickly from refrigerators to electronics, adopting the name Raytheon and mass‑producing gas‑filled tubes and “battery eliminators” that allowed radios to run from household current. Raytheon would become a radar and sensing powerhouse and later a major defense contractor. Bush’s fingerprints are therefore present in the sensor chains that would, by mid‑century, underpin aerial surveillance and the capture of anomalies. (RTX corporate history; Wikipedia summary; EBSCO overview). (RTX)

A new kind of mobilization: NACA, NDRC, and OSRD

By the late 1930s Bush had moved onto the national stage. He served on the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics beginning in 1938 and chaired it from 1939 to 1941. Even more consequential was his June 1940 meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt that yielded the National Defense Research Committee. The next year, Roosevelt created the Office of Scientific Research and Development with Bush as director, placing the nation’s scientific arsenal under coordinated civilian leadership that reported directly to the White House. Under this arrangement thousands of scientists worked on radar, anti‑submarine warfare, mass‑produced penicillin, and computational methods. The OSRD became the hub that linked universities, industry, and the services. In administrative design and scope, nothing like it had existed before. (Wikipedia summaries with primary references; NAS memoir). (Wikipedia)

Radar, proximity fuzes, and the sensing revolution

Radar’s accelerated maturation at MIT’s Radiation Laboratory is the hinge on which modern aerial detection turns. Spurred by the British Tizard Mission’s magnetron gift and funded through Bush’s NDRC and OSRD, the Rad Lab produced microwave radars for gun laying and aircraft interception, along with LORAN long‑range navigation and early airborne warning concepts. These systems scaled into continental surveillance in the 1950s and planted the hardware and doctrine for discerning unknowns in the airspace. In parallel, Bush enabled NDRC “Section T,” led by Merle Tuve at the Carnegie Institution, to solve the proximity fuze, which transformed anti‑aircraft accuracy and depended on miniaturized radio sensing that survived massive g‑forces. All of this was precisely the sort of fast‑loop, high‑sensitivity instrumentation that later U.S. operators would use to log unidentified tracks and “radar‑visual” anomalies. (MIT Lincoln Laboratory history; MIT Rad Lab overview; Carnegie Science; HistoryNet overview). (Lincoln Laboratory)

Manhattan Project and strategic governance

Bush’s OSRD initially incubated atomic fission work under the “S‑1” umbrella, then helped midwife the Army’s Manhattan Engineer District. He and James B. Conant sat on the Military Policy Committee that oversaw the project’s highest decisions, giving him a direct hand in moving atomic research from academic exploration to industrial‑scale production. This episode mattered to UAP history indirectly. It cemented a template for special‑access science, priority allocation, and deeply compartmented record‑keeping. That template later shaped how sensitive sensor data, whether nuclear or anomalous, could be siloed within tightly controlled channels. (DOE/OSTI Manhattan Project histories; MPC accounts). (OSTI)

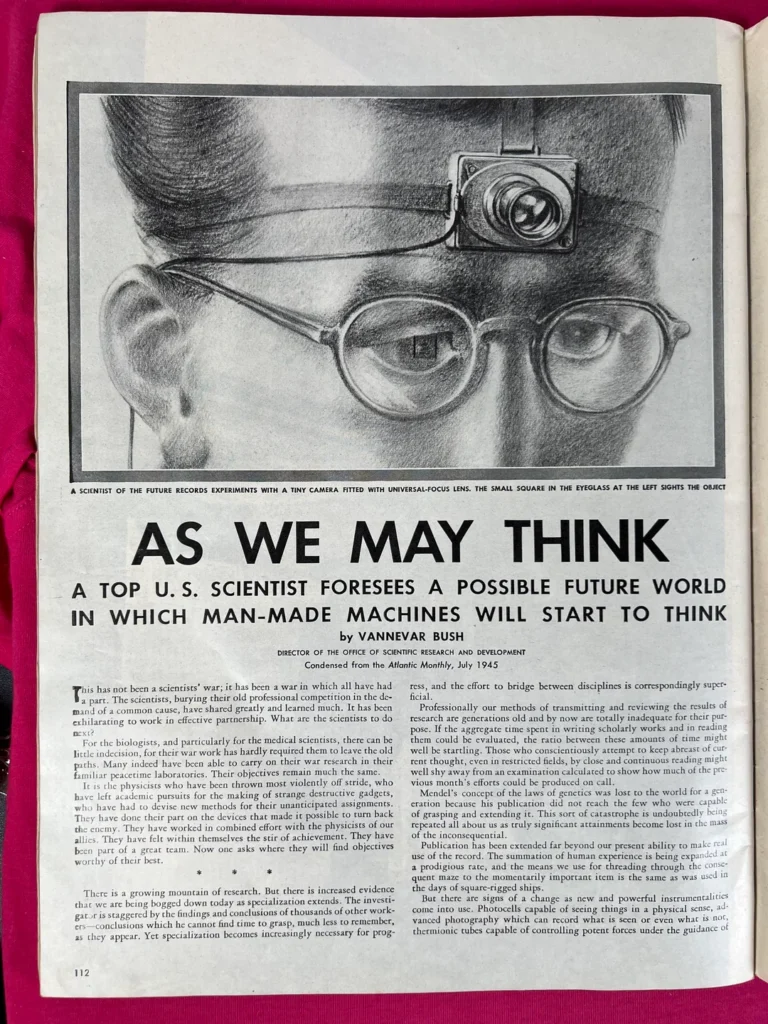

“As We May Think” and the memex

Immediately after the war Bush published “As We May Think,” arguing that scientists emerging from secrecy should now perfect “pacific instruments” for thought. He sketched the memex, a desk‑sized machine that used microfilm, associative “trails,” and annotation to organize human knowledge at the speed of thought. The essay inspired generations of information architects and hypertext pioneers. In UAP research, the memex reads like a prophecy for how to thread disparate radar logs, pilot reports, spectroscopic records, and FOIA releases into coherent trails that can be shared and re‑examined. That sensibility animates today’s digital UAP observatories and open‑source analysts who insist that discovery is often a matter of linkage rather than a single sensor. (The Atlantic, 1945). (The Atlantic)

Science, the Endless Frontier and the birth of the NSF

At Roosevelt’s request in late 1944, Bush drafted the report “Science, the Endless Frontier,” delivered in July 1945. He argued for sustained federal support of basic research, mechanisms to cultivate scientific talent, and the diffusion of knowledge for health, prosperity, and security. The report is widely regarded as the intellectual charter for the National Science Foundation, established in 1950. In the UAP context, Bush’s core idea was that national vitality depends on curiosity‑driven science coupled to robust publication and archiving. That logic underwrites the expectation that anomalous data should be studied with the same seriousness as any vexing natural phenomenon. (FDR letter; archived report; NSF retrospectives). (The American Presidency Project)

From OSRD to the Research and Development Board

As the war ended, Bush steered the wind‑down of OSRD while insisting the nation not lose its research momentum. He chaired the Joint Research and Development Board of the Army and Navy in 1946–1947 and then the Department of Defense’s Research and Development Board in 1947–1948. President Truman’s letter confirming his RDB appointment captured the continuity he represented: civilian science leadership guiding military modernization. The RDB presided over a period when radar networks became peacetime infrastructure, and the Air Force consolidated its approach to unidentified aerial reports. (NAS memoir; Truman Library and Presidency Project). (NAS)

Honors and later years

Bush’s influence was acknowledged across engineering and policy communities. He received the Public Welfare Medal of the National Academy of Sciences in 1945, the National Medal of Science in 1963, and many other honors. He served as president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington from 1939 to 1955, later as chairman of the MIT Corporation, and he wrote reflective books including “Endless Horizons” (1946), “Science Is Not Enough” (1967), and “Pieces of the Action” (1970). He died on June 28, 1974, in Belmont, Massachusetts, after a stroke and pneumonia. His legacy includes the National Science Board’s Vannevar Bush Award, given annually to an individual whose public service in science has “benefited the Nation.” (NAS memoir; National Medals Foundation; UCSB Presidency Project; Britannica). (NAS)

Bush and UAP: What his system enables

The sensing architectures Bush accelerated make UAP more knowable. By fastening the wartime university‑industry complex to radar, radio navigation, and electronic countermeasures, Bush helped string together a lattice of emitters and receivers that could turn sky and sea into data. That lattice grew into continental early warning networks and, with the advent of digital computation, into multivariate sensor fusion. UAP episodes that include “radar‑visual” corroboration are, in a meaningful sense, descendants of the Rad Lab’s ethos of instrumented reality. When modern operators capture anomalous tracks that comport across independent systems, they are reading the dials on Bush’s legacy. (MIT Rad Lab histories; Lincoln Laboratory overview). (Wikipedia)

The information culture he advocated is the antidote to mystery without method. “As We May Think” insisted that knowledge should be organized along associative trails and shared to expedite discovery. The memex spirit aligns with the best contemporary UAP work, which emphasizes linked archives, reproducible analyses, and the careful threading of heterogeneous records. In an era of overwhelmed analysts, Bush’s call to prioritize the tools of thought remains a crisp guide. (The Atlantic, 1945). (The Atlantic)

The secrecy template he normalized also explains why UAP debates often fixate on access. OSRD and the Manhattan Project set enduring practices for compartmentation, need‑to‑know, and special‑access channels. Those practices protected crucial wartime programs. They also trained generations of officials to segment unusual data, which has sometimes left anomalous observations stranded in narrow units or highly classified bins. The lesson for UAP work is to push for structured transparency and for scientific review mechanisms that can straddle classification without neutering inquiry. That is a Bushian move as well, since his postwar program demanded wide diffusion of knowledge consistent with security. (OSTI Manhattan Project summaries; FDR letter; “Endless Frontier”). (OSTI)

About the MJ-12 claims. Beginning in the 1980s, anonymously circulated papers alleged the existence of a “Majestic 12” group and often listed Bush among its members. The FBI summarized an Air Force inquiry that concluded that these papers were fake, and the National Archives reports that searches of presidential and defense holdings found no corroboration. Despite that official posture, a minority of UAP researchers dispute the inauthenticity finding. Nuclear physicist Stanton T. Friedman assembled a pro‑authenticity case in Top Secret/MAJIC, and Robert M. Wood later presented additional arguments. A neutral description for a biographical article is therefore: the MJ‑12 corpus is widely regarded as inauthentic by official evaluations, and many historians yet remains disputed within a portion of the UAP research community. (FBI)

Chronology

- 1890–1916. Born in Everett, Massachusetts; BS and MS from Tufts; doctoral degree in electrical engineering via MIT and Harvard. The mix of shop‑floor work and advanced theory becomes his signature approach to solving practical sensing problems. (Britannica; NAS memoir). (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- 1919–1931. Joins MIT, develops the differential analyzer. Recruits and inspires Claude Shannon, whose logic‑circuit thesis foreshadows digital signal processing central to modern sensor suites that underpin UAP data collection. (MIT Museum; MIT News). (MIT Museum)

- 1922. Co‑founds Raytheon, which becomes a leader in radar and missile sensors. Bush’s entrepreneurial wing ties academic insight to manufactured sensing hardware. (RTX history). (RTX)

- 1938–1941. Serves on and chairs NACA. Builds relationships with Army Air Corps and Navy Bureau of Aeronautics that will be crucial for organizing radar and airborne warning systems. (Wikipedia/NASA histories). (Wikipedia)

- 1940–1945. Chairs NDRC and directs OSRD. MIT’s Radiation Laboratory, funded under NDRC and OSRD, accelerates microwave radar, gun‑laying radars like SCR‑584, and airborne early warning concepts. These become the backbone of later airspace surveillance that routinely records anomalies. (MIT Lincoln Laboratory; MIT Rad Lab overview). (Lincoln Laboratory)

- 1940–1945. Authorizes NDRC “Section T” under Merle Tuve to solve the proximity fuze, an achievement that fused miniaturized radio detection with wartime lethality. This work propelled broader electronic sensing and miniaturization trends. (Carnegie Science). (Carnegie Science)

- 1942–1945. Helps steer atomic work from OSRD S‑1 into the Army’s Manhattan District. The Military Policy Committee process institutionalizes special‑access science. (OSTI histories). (OSTI)

- July 1945. Publishes “As We May Think” and “Science, the Endless Frontier.” The first calls for better memory tools, the second lays out federal support for research and talent that culminates in the NSF. Both shape how anomalous evidence should be gathered and curated. (The Atlantic; archived report; NSF retrospective). (The Atlantic)

- 1946–1948. Chairs the JRDB and then the DoD’s Research and Development Board. This is the bridge from wartime instrumentation to peacetime networks that will feed official UAP investigations. (NAS memoir; Truman Library). (NAS)

- 1950–1969. Institutional successors in the Air Force conduct Project Sign, Grudge, and Blue Book, all of which rely on the sensor webs and reporting structures that Bush’s system normalized. (National Archives; USAF fact sheet). (National Archives)

- 1963. Receives the National Medal of Science. Recognition reflects his unique synthesis of engineering, policy, and institution‑building. (National Medals Foundation; UCSB Presidency Project). (nationalmedals.org)

- 1974. Dies in Belmont, Massachusetts. Eulogists emphasize that “no American has had greater influence in the growth of science and technology” than Bush. The modern approach to UAP inquiry still rests on his pillars of sensing and memory. (NAS memoir; Britannica). (NAS)

- 1984–1988. The anonymously circulated “MJ‑12” papers name Bush as a member of a supposed secret committee. The FBI cites an Air Force determination that the papers were fake, and the National Archives reports no corroborating records. A minority of UAP researchers, most visibly Stanton T. Friedman, continue to defend some documents, so the status is best characterized as “officially inauthentic, disputed by some researchers.” (FBI)

Assessing his impact on UAP studies

- Institutional architecture. Bush’s insistence that national security requires organized, civilian‑led science produced the arrangements that could turn fleeting aerial events into durable records. The OSRD model showed how to fund and coordinate cross‑sector research quickly, an approach that later helped the services set up dedicated study programs for reports of unknowns. (Wikipedia overview citing primary sources; NAS memoir). (Wikipedia)

- Instrumentation. Radar engineering at the Rad Lab and the proximity fuze program taught engineers to capture, filter, and correlate noisy, high‑velocity phenomena. Those lessons are the DNA of modern UAP sensor stacks that combine radar, IR, EO/visible, and telemetry. (MIT Rad Lab histories). (Wikipedia)

- Information science. “As We May Think” framed a philosophy of scientific memory. UAP work requires precisely this: craft trails through pilot narratives, radar returns, and lab results. Bush’s memex is the conceptual ancestor of the databases and toolchains used by today’s independent and official investigators. (The Atlantic, 1945). (The Atlantic)

- Policy ethos. “Science, the Endless Frontier” made the case that basic research is a public good. The implication for UAP is that studying anomalies should not be shunted to rumor or purely classified channels. It belongs in a continuum with atmospheric physics, sensor engineering, and cognitive science, open to peer review where possible. (Archived report; NSF 75th). (Internet Archive)

- Separating documentation from allegation. While some late‑20th‑century narratives sought to attach Bush’s name to secret UAP committees, official archival releases make clear that the famous “MJ‑12” materials are not authentic. Bush’s real achievements need no embroidery. The better way to honor his relevance to UAP is to use his methods: build better instruments, keep better records, and cultivate talent to ask hard questions. (FBI Vault; USAF and National Archives materials). (FBI)

Conclusion: The Bush template for tackling anomalies

Vannevar Bush’s life shows that the path to understanding the unknown is to build systems that leave less unknown. He brought order to wartime research not to constrain discovery but to accelerate it. He saw that memory was as strategic as measurement. And he practiced the kind of institutional craftsmanship that makes gnarly problems tractable without smothering curiosity. For UAP, that is the enduring lesson. Treat anomalies as invitations to engineer better sensors, to organize collaborative analysis, and to expand the archive so future investigators can follow the trail. That is the Bush way, and it remains the surest route from wonder to knowledge. (NAS memoir; MIT Lincoln Laboratory; NSF retrospectives). (NAS)

References

Britannica. (n.d.). Vannevar Bush. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Vannevar-Bush (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Bush, V. (1945, July). As we may think. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/ (The Atlantic)

Bush, V. (1945). Science, the Endless Frontier. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://archive.org/download/scienceendlessfr00unit/scienceendlessfr00unit.pdf (Internet Archive)

Bush, V. (1970). Pieces of the Action. Morrow. (Open copy) https://gwern.net/doc/history/1970-bush-piecesoftheaction.pdf (Gwern)

Carnegie Science. (2020s). Developing the proximity fuze. https://carnegiescience.edu/news/developing-proximity-fuze (Carnegie Science)

FBI. (n.d.). Majestic 12 — The Vault. https://vault.fbi.gov/Majestic%2012 (FBI)

MIT Lincoln Laboratory. (n.d.). MIT Radiation Laboratory. https://www.ll.mit.edu/about/history/mit-radiation-laboratory (Lincoln Laboratory)

MIT Museum. (n.d.). Differential analyzer collections entries. https://mitmuseum.mit.edu/collections/object/GCP-00003618 and related items (MIT Museum)

MIT News. (2001, Feb. 27). MIT Professor Claude Shannon dies. https://news.mit.edu/2001/shannon (MIT News)

NAS (Wiesner, J. B.). (1979). Vannevar Bush. Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, 50. https://www.nasonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/bush-vannevar.pdf (NAS)

National Archives. (2019, Dec. 5). Public interest in UFOs persists 50 years after Project Blue Book. https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/project-blue-book-50th-anniversary (National Archives)

National Archives. (2024). Project BLUE BOOK. https://www.archives.gov/research/military/air-force/ufos (National Archives)

National Medals of Science and Technology Foundation. (n.d.). Vannevar Bush. https://nationalmedals.org/laureate/vannevar-bush/ (nationalmedals.org)

NSF. (2020s). Science — the Endless Frontier at 75. https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/2023-04/EndlessFrontier75th_w.pdf (NSF Resources)

OSTI/DOE. (n.d.). Office of Scientific Research and Development; S‑1/Manhattan Project pages. https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/People/CivilianOrgs/osrd.html; and related S‑1 pages. (OSTI)

RTX (Raytheon). (2022, July 6). 100 years of era‑defining innovation. https://www.rtx.com/news/2022/07/01/raytheon-100-anniversary (RTX)

Truman Library & Museum. (1947). Letter to Dr. Vannevar Bush upon his appointment as Chairman, RDB. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/192/letter-dr-vannevar-bush-upon-his-appointment-chairman-research-and (Harry S. Truman Presidential Library)

U.S. Air Force. (n.d.). Unidentified Flying Objects and Air Force Project Blue Book. https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/104590/unidentified-flying-objects-and-air-force-project-blue-book/ (U.S. Air Force)

Wikipedia community summaries used for date checks and role overviews, with primary citations listed on their pages: Vannevar Bush; MIT Radiation Laboratory; S‑1 Executive Committee. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vannevar_Bush; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MIT_Radiation_Laboratory; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S-1_Executive_Committee (Wikipedia)

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (1988). Majestic 12 [FOIA release]. FBI Vault. https://vault.fbi.gov/Majestic%2012 (FBI)

National Archives and Records Administration. (2024, June 25). Project BLUE BOOK (U.S. Air Force) and related records [includes “Majestic 12” reference information]. https://www.archives.gov/research/military/air-force/ufos (National Archives)

Friedman, S. T. (1996). Top Secret/MAJIC: Operation Majestic‑12 and the United States Government’s UFO Cover‑Up. New York, NY: Marlowe & Company. https://archive.org/details/topsecretmajic0000frie (Internet Archive)

Wood, R. M. (2001, July). Mounting evidence for authenticity of MJ‑12 documents [Paper presented at the MUFON International Symposium]. Internet Archive text. https://archive.org/stream/majiall337/rmwood_mufon2001_djvu.txt (Internet Archive)

U.S. General Accounting Office. (1994). Comments on Majestic 12 material [Letter report]. https://www.gao.gov/assets/154832.pdf (U.S. Government Accountability Office)

SEO keywords

Vannevar Bush biography, Vannevar Bush UAP, Office of Scientific Research and Development, MIT Radiation Laboratory radar, Science the Endless Frontier, memex As We May Think, Raytheon founders, NDRC proximity fuze, Manhattan Project policy, National Science Foundation history, UAP radar detection history, Majestic 12 FBI Vault, Project Blue Book context, Vannevar Bush MJ‑12, Majestic 12 disputed, Stanton Friedman Top Secret/MAJIC, MJ‑12 authenticity debate, FBI MJ‑12 determination, National Archives MJ‑12 reference report, UAP history and Vannevar Bush.