In the twilight of World War II, as the ruins of Europe smoldered, a German engineer named Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun stepped forward from the wreckage with a dream that would shape the modern age: to lift humanity beyond the Earth.

His Saturn V rocket would one day carry men to the Moon. Yet, beneath the myth of scientific triumph lies a deeper, stranger current, one that flows through the esoteric underworld of Nazi-era mysticism, Cold War secrecy, and the birth of modern UFO lore.

Von Braun’s life sits at the junction of science, ideology, and something almost metaphysical. He was a visionary engineer and a man deeply entangled in one of history’s darkest regimes.

And around his story swirls an aura of myth, where rocketry, religion, and even the occult intersected in ways that would echo into UFO discourse and New Age cosmic philosophy for decades to come.

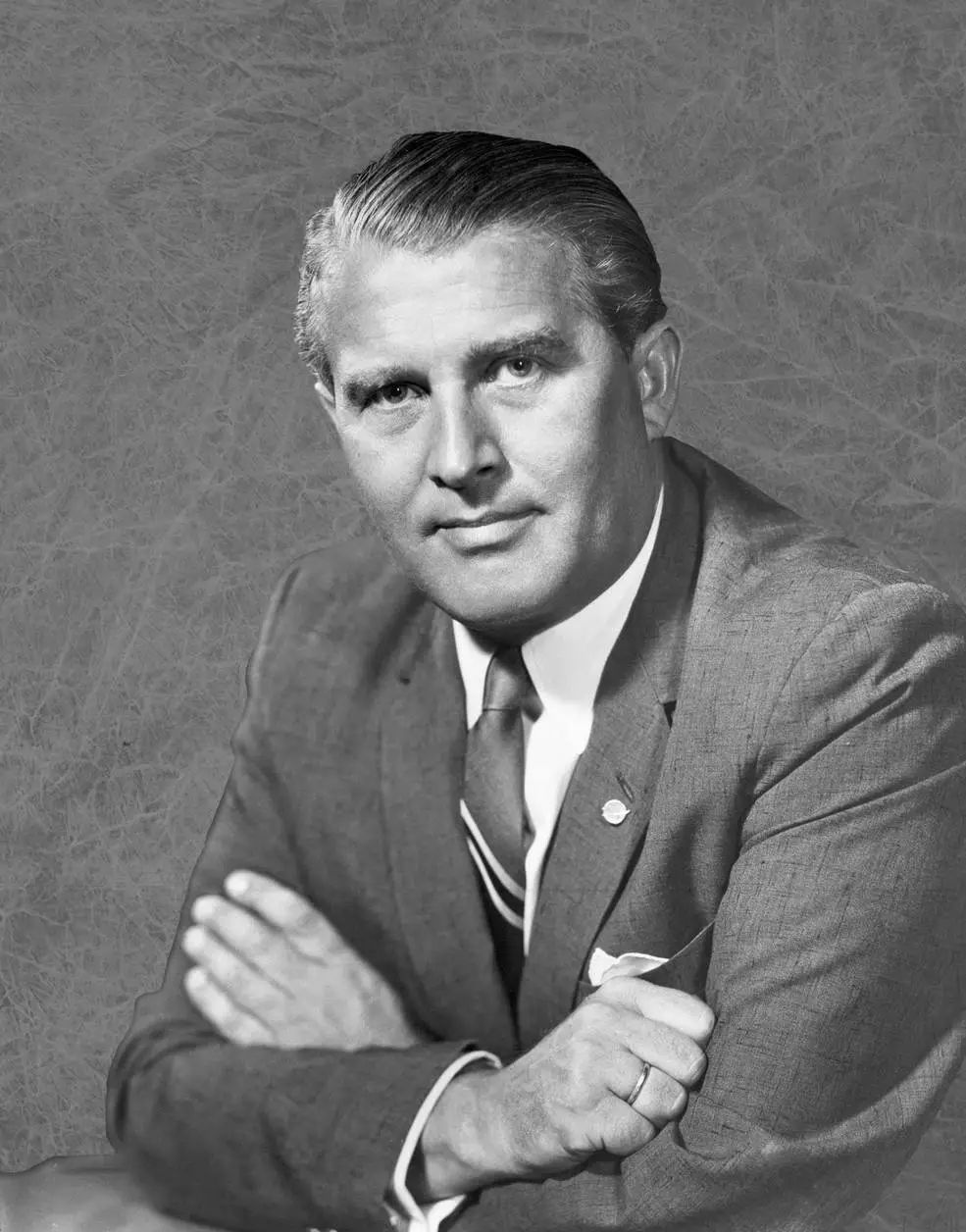

The Rocket Dreamer

Born in 1912 in Wirsitz (now Wyrzysk, Poland), von Braun was the son of Prussian aristocrats. His father, Magnus, served in the Weimar government; his mother, Emmy von Quistorp, introduced him to music, art, and theology. But Wernher’s true obsession began when he read Hermann Oberth’s Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Planetary Space), a text that transformed adolescent curiosity into vocation.

By his early twenties, von Braun had joined the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (Society for Space Travel), experimenting with liquid-fuel rockets and dreaming of interplanetary flight. Yet, when the German military saw the potential of such weapons, von Braun’s dream became the Reich’s tool.

He accepted a research commission under the Army’s Ordnance Department in 1932 and soon became technical director of Peenemünde, the Baltic testing site that would birth the A-4, later known as the V-2, the world’s first long-range ballistic missile (NASA biography).

The V-2 was a technological masterpiece, and a moral catastrophe. Tens of thousands of forced laborers died building them in underground camps like Mittelwerk. Von Braun would later claim his allegiance was to rocketry, not ideology, but records confirm his membership in both the Nazi Party (1937) and the SS (1940) (Britannica).

The Occult Under the Reich

To understand von Braun’s world, one must see the peculiar spiritual atmosphere that surrounded the Nazi scientific elite. In the 1930s, Himmler’s SS fostered an ideology steeped in Teutonic mysticism, Aryan mythology, and pseudo-occult science.

Institutions like the Ahnenerbe sought to uncover ancient “lost knowledge” believed to prove a cosmic origin for the Aryan race. They mixed runic symbols, astrology, and early pseudoscience with real technological research.

While von Braun himself was an engineer rather than an occultist, he operated within a culture that blurred the line between physics and metaphysics.

Peenemünde engineers reportedly referenced the V-2’s “power to reach the heavens” with quasi-religious reverence. Historian Michael Allen notes that “for von Braun, the rocket was not just a machine, it was a ladder to transcendence.”

The Nazi fascination with cosmic origins, the Vril and Thule mythos of hidden energy and ancient civilizations, formed part of the milieu around him.

Later popular writers, from Louis Pauwels to Jacques Bergier in The Morning of the Magicians, would link von Braun’s circle to these mythic ideas, seeing in their quest for propulsion a disguised spiritual hunger: to pierce the veil between Earth and the heavens

Operation Paperclip: Science, Secrecy, and Salvation

When the Third Reich collapsed, von Braun and his team chose to surrender to American rather than Soviet forces. They were swiftly absorbed into Operation Paperclip, a covert U.S. program to transfer German scientists to America despite their Nazi affiliations (National Archives).

Von Braun arrived in 1945, bringing his technical genius, and his past. In Fort Bliss and later at the White Sands Proving Ground, he resumed rocket testing, now under an American flag. The U.S. government sanitized his record, prioritizing Cold War advantage over moral clarity.

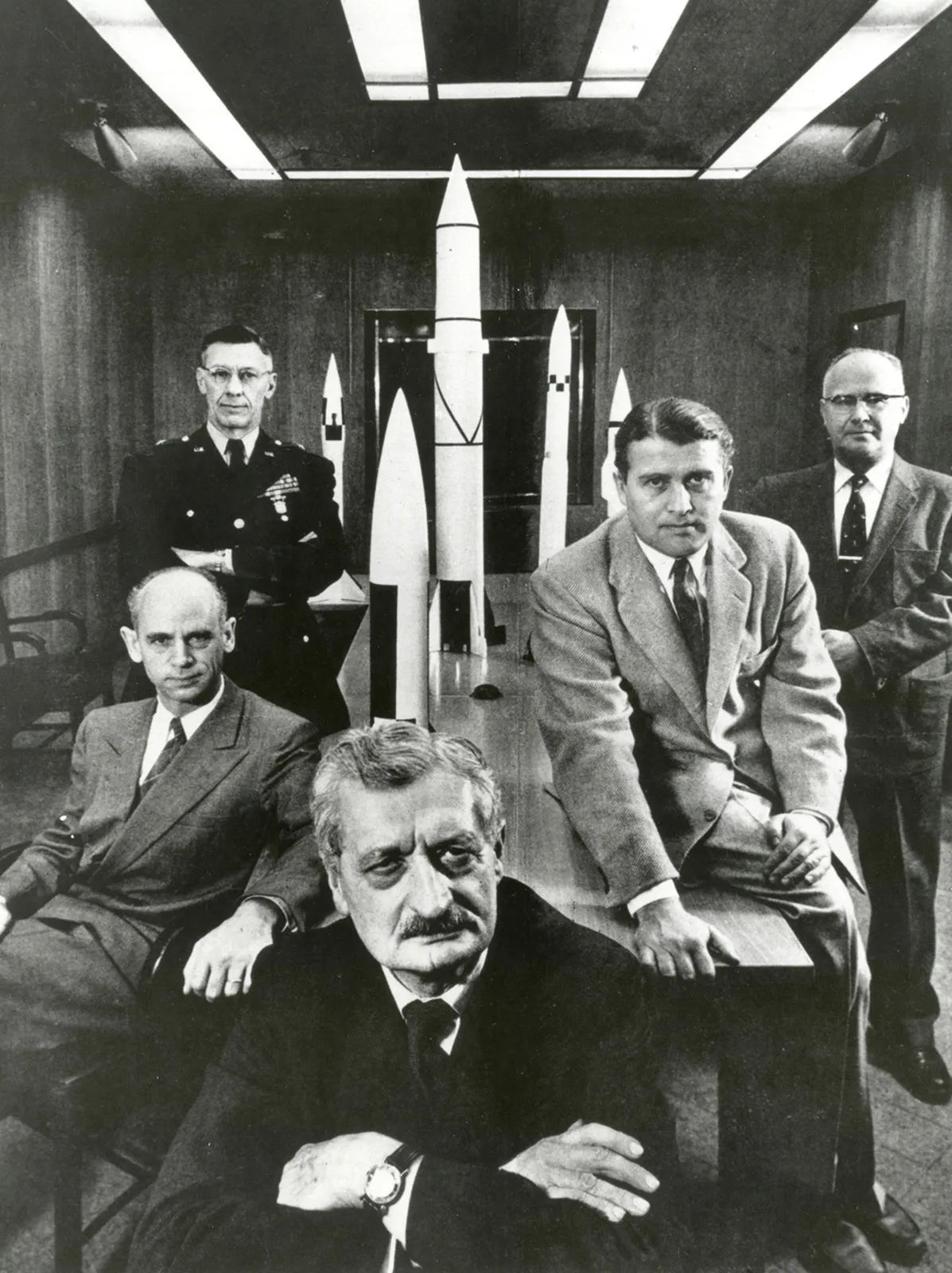

At Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, von Braun led development of the Redstone and Jupiter rockets. His team’s innovations eventually powered Explorer I, America’s first satellite, in 1958.

Two years later, the group became part of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, where von Braun directed the creation of the Saturn V, the rocket that sent Apollo 11 to the Moon in July 1969.

His public persona was reshaped from “Hitler’s rocket man” to “America’s space visionary.” Collaborations with Walt Disney in the 1950s, such as Man in Space and Mars and Beyond – introduced his ideas to millions, framing cosmic exploration as humanity’s spiritual destiny.

Mysticism and the Machine

As von Braun’s scientific career ascended, so too did his philosophical and spiritual reflections. He often spoke of space travel as a means to glimpse divine creation. In later writings he invoked God not as a dogmatic figure, but as a cosmic architect whose laws of physics invited discovery. “Science,” he wrote, “is mankind’s effort to understand the creation of God.”

This religious humanism, tempered by an engineer’s precision, would later resonate with astronauts like Edgar Mitchell, who, during the Apollo 14 mission, experienced what he called a samadhi, or unity consciousness.

Mitchell went on to found the Institute of Noetic Sciences, dedicated to exploring consciousness and the frontier between science and spirituality.

Mitchell cited von Braun’s vision as formative, remarking that humanity’s reach into space inevitably provoked metaphysical questions about the universe and our place in it. Von Braun’s rhetoric about humanity’s “cosmic purpose” anticipated this shift: from space as territory to space as revelation.

Yet, in the undercurrents of this narrative, one can still trace the old mystic impulses of the German esoteric tradition, repackaged through the lens of Cold War optimism. The occult had gone underground, resurfacing as cosmic wonder.

From Rockets to Flying Saucers

The postwar era also birthed modern UFO culture. Many early sightings coincided with the rapid development of jet propulsion and missile testing.

Some researchers, noting the timing, have speculated that von Braun’s experiments at White Sands may have seeded early “flying saucer” reports in the American Southwest.

Declassified U.S. Air Force files from Project Sign (1948) and Project Blue Book (1952–69) reveal that some UFO cases occurred near missile ranges and launch facilities (National Archives Blue Book Collection). While most were explained as misidentifications, the coincidence reinforced the perception that cutting-edge aerospace and the unexplained were entwined.

Von Braun himself never publicly endorsed UFO reality, but his silence fed speculation. Some later accounts, apocryphal but persistent, suggested he privately acknowledged “phenomena beyond our comprehension.”

One of his close collaborators, Dr. Carol Rosin, would later claim von Braun warned her of a future “cosmic threat” narrative that governments might use to militarize space. Though unverifiable, her testimony helped cement von Braun’s image as a reluctant prophet of the UFO age.

The Occult Legacy in Modern Space Culture

The mid-20th century saw a merging of rocket science, Cold War secrecy, and the occult imagination. Figures like Jack Parsons, the American rocketeer and occultist who co-founded JPL and practiced Thelemic magick under Aleister Crowley, embodied this blend most vividly. Though Parsons and von Braun never met, they had an intercontinental correspondence as teenagers where they exchanged ideas about rocketry. They shared information and experimental notes for years via letters and phone calls before going their separate ways as adults, with von Braun working for the German army and Parsons for CalTech. (Britannica)

Parsons’ experiments at Pasadena and von Braun’s at Peenemünde were, in a strange symmetry, twin expressions of humanity’s drive to ascend a literal and metaphoric striving for the heavens. Their legacies intertwined in the public mind, feeding a generation of ufologists and science fiction writers who saw rockets and UFOs as two sides of the same mystery.

Writers like Arthur C. Clarke and later Jacques Vallée (author of Passport to Magonia) interpreted this blend of technology and mysticism as a key to understanding not just UFOs, but consciousness itself. Vallée and others in the 1970s pointed to von Braun’s symbolic role as humanity’s Prometheus, bringing fire from the gods, at immense moral cost.

Ethics, Ambition, and Afterlife

By the 1970s, von Braun had become both a national hero and a source of ethical unease. The same hands that guided humanity to the Moon had also overseen weapons built by enslaved labor. Critics in the press and academia wrestled with the contradiction. He responded by retreating into advocacy for peaceful space exploration and education. In 1975 he co-founded the National Space Institute, later merging into the National Space Society, to promote international cooperation in space.

He died of pancreatic cancer in 1977, aged 65, leaving behind not only blueprints for rockets but a mythos that still haunts aerospace culture.

Influence on Modern UFO and Consciousness Studies

Von Braun’s vision of space as a moral frontier inspired not only scientists but also a generation of thinkers who saw in UFOs a mirror for human evolution. Astronaut Edgar Mitchell, physicist Hal Puthoff, and theorists of consciousness often cited the space program as a gateway to metaphysical thought.

Mitchell, in particular, linked the technological breakthroughs of the Apollo era to a spiritual awakening, a realization that advanced civilizations, perhaps those behind UAPs, might operate through principles as yet unknown to human science. This fusion of empirical exploration and transcendental philosophy echoes von Braun’s belief that humanity’s destiny lay among the stars.

Von Braun’s association with the occult is best understood as cultural, not personal. He lived within a world that blurred myth, science, and state ideology; his later American career rechanneled that same fusion into a vision of cosmic progress. The mystic undertones never vanished, they evolved.

Legacy and Reflection

Wernher von Braun’s story is one of dualities: faith and reason, vision and complicity, heaven and hell.

His rockets were born in tunnels dug by slaves, yet they carried humankind to the Moon. His early life unfolded amid occult nationalism; his later years amid scientific idealism. Between them stretches the paradox of the 20th century itself.

Today, when NASA probes scan distant worlds and the Pentagon acknowledges unidentified anomalous phenomena, von Braun’s legacy feels strangely prophetic.

He built the machines that opened the heavens, but he also helped forge the mythic language, of ascension, transcendence, and otherworldly contact, that would define the UFO age.

References

- NASA: Wernher von Braun Biography (NASA)

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Wernher von Braun (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- National Archives: Operation Paperclip Files (Foreign Scientist Case Files)

(National Archives). Also: (National Archives) - NASA History Office: Saturn V Development Plan (NASA. Also: (NASA)

- Disney Archives: Von Braun and Walt Disney Collaboration (National Air and Space Museum). Also: https://archive.org/details/MSFC-6522327 (image brief) (Internet Archive)

- Institute of Noetic Sciences: Edgar Mitchell Biography (IONS). Also: (New Mexico Museum of Space History)

- Smithsonian: Nazi Occult and Science in the Third Reich (Smithsonian Magazine).

Also: Smithsonian: How much did Von Braun Know (Smithsonian) - Project Blue Book Records, National Archives (National Archives). Also: (osi.af.mil)

SEO Keywords

Wernher von Braun occult, Nazi mysticism and science, Operation Paperclip, Edgar Mitchell consciousness, von Braun UFO influence, Ahnenerbe occult research, Peenemünde V-2 rockets, NASA Saturn V history, von Braun spiritual philosophy, Nazi esotericism and space exploration.